-

Investigations of the cosmological gravitational-wave background hold profound significance. This background radiation predominantly originates from primordial gravitational-wave sources within the early universe, such as inflationary quantum fluctuations, coupled cosmological perturbations, first-order phase transitions, and topological defects, thus encoding critical information about the primordial universe (see, e.g., Ref. [1] for a review and references therein). Moreover, gravitational waves constitute linear cosmological tensor perturbations, whose evolutionary trajectory is governed by initial conditions, specifically whether they manifest adiabatic or homogeneous characteristics [2, 3]. The adiabatic initial conditions apply when gravitational waves originate as a thermalized component from inflaton decay. In contrast, the homogeneous ones are the physically motivated choice for the unperturbed backgrounds generated by the most common sources, such as those mentioned above. Therefore, upon detection of such gravitational waves, we shall not only decipher physical processes operative during the universe’s infancy but also elucidate the fundamental mechanisms governing cosmic inception.

The cosmological gravitational-wave background is a prime observational target for direct detection by gravitational-wave observatories. In the high-frequency regime, terrestrial interferometers have recently imposed rigorous upper bounds on the energy-density fraction spectrum of the stochastic gravitational-wave background [4]. For the nanohertz-frequency band, multiple pulsar timing array (PTA) collaborations have reported compelling evidence for a stochastic background [5−8]. Regarding the millihertz-frequency band, space-borne gravitational-wave detectors are projected to conduct precision measurements of the stochastic background within the upcoming decade [9−11].

Complementary to the direct detection of gravitational waves, cosmological probes employing the cosmic microwave background (CMB) and baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) measurements provide indirect constraints on the cosmological gravitational-wave background [12]. The CMB detects such gravitational waves because they enhance the expansion rate of the universe during the epoch of photon decoupling. BAO detects them because they suppress the growth of matter density perturbations. Leveraging the Planck 2018 CMB data alongside several BAO datasets, Ref. [13] established observational upper bounds on the gravitational-wave energy density, depending on initial conditions that are either adiabatic or homogeneous. Were these constraints further integrated with PTA datasets, they would yield tightened observational bounds on the gravitational waves from inflationary fluctuations [14−16], first-order phase transitions [17], and the induced gravitational waves [18−22].

The recently unveiled BAO measurements from Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) Data Release 2 (DR2) [23] may prompt revisions to existing constraints on the cosmological gravitational-wave background. Notably, DESI has not only delivered state-of-the-art BAO measurements but also uncovered strong evidence for dynamical dark energy. Through synergistic analysis of these data with Planck 2018 CMB observations, Ref. [24] recently established an upper bound on the tensor-to-scalar ratio, which quantifies the spectral amplitude of primordial gravitational waves in the ultra-low frequency band, i.e.,

$ f\lesssim10^{-16} $ Hz. Nevertheless, in higher frequency bands, detailed investigations into the gravitational-wave energy density remain conspicuously absent in current literature, a gap designated as a paramount focus of the present study.Next-generation CMB and BAO surveys hold considerable promise for probing the cosmological gravitational-wave background with unprecedented precision, thereby establishing significantly tighter constraints on the gravitational-wave energy density. Relative to extant facilities such as the Planck satellite, forthcoming observatories, notably the LiteBIRD satellite [25] and CMB Stage-IV (S4) ground array [26], will deliver substantially refined measurements of the CMB polarization. Similarly, next-generation spectroscopic surveys including the China Space Station Telescope (CSST) [27] are anticipated to execute BAO observations of enhanced spatial coverage and precision beyond DESI's capabilities. Through synergistic analysis of these datasets, we project stringent refinements to constraints on cosmological gravitational waves. This constitutes a complementary core objective of the present study.

This investigation pioneers a dual-pronged analytical framework, simultaneously constraining the gravitational-wave physical energy-density fraction today, denoted by

$ \Omega_{\mathrm{gw}}h^{2} $ , through state-of-the-art cosmological observations and projecting detection thresholds for next-generation observatories. Incorporating the phenomenological consequences of dynamical dark energy, we derive rigorous upper bounds on$ \Omega_{\mathrm{gw}}h^{2} $ by combining the latest CMB and BAO data, under adiabatic versus homogeneous initial condition paradigms. These observationally derived constraints are subsequently benchmarked against the ΛCDM cosmology. We further quantify prospective sensitivity enhancements achievable through the synergistic exploitation of next-generation CMB measurements alongside CSST BAO observations. The resultant framework establishes novel upper bounds on cosmological gravitational-wave backgrounds across the$ f \gtrsim 10^{-15} $ Hz domain, delineating definitive constraints for physical processes occurring in the early universe.The paper is structured as follows. Section II presents the influence of cosmological gravitational waves on CMB and BAO under adiabatic and homogeneous initial conditions. Section III describes data analysis methods and derives upper limits on

$ \Omega_{\rm{gw}}h^{2} $ from current CMB and BAO observations. Section IV outlines cosmological forecasting methods to assess the sensitivity achievable with future CMB and BAO observations. Finally, Section V provides conclusions and discussion. -

Cosmological gravitational waves with frequencies above

$ 10^{-15} $ Hz can leave characteristic imprints on both the CMB and matter power spectra, making them potentially constrained by CMB and BAO observations. On one hand, as a form of radiation, these gravitational waves enhance the cosmic expansion rate at photon decoupling, thereby altering the small-scale angular power spectrum of the CMB. On the other hand, being free-streaming radiation, they suppress the growth of density perturbations, consequently modifying the matter power spectrum observable through BAO measurements.Gravitational waves, as cosmological tensor perturbations, satisfy evolution equations identical in form to those for massless neutrinos, but the solutions to these equations depend critically on the choice of initial conditions. The necessary formalism involves deriving the linear perturbations of the Einstein and fluid-conservation equations (see details in, e.g., Ref [13]). The cosmic fluid includes not only photons, neutrinos, baryons, and dark matter, but also gravitational waves. The linear perturbations related to gravitational waves are characterized by the density (

$ \delta_{\rm gw} $ ), velocity ($ \theta_{\rm gw} $ ), and shear ($ \sigma_{\rm gw} $ ) perturbations in the synchronous gauge. Consequently, one obtains a system of four perturbed Einstein equations, supplemented by a corresponding set of fluid conservation equations for each individual species. For the gravitational waves, which can be treated as a collisionless relativistic gas of gravitons, the fluid conservation equations are specifically given by [12, 13]), and shear ($ \sigma_{\rm gw} $ ) perturbations in the synchronous gauge. Consequently, one obtains a system of four perturbed Einstein equations, supplemented by a corresponding set of fluid conservation equations for each individual species. For the gravitational waves, which can be treated as a collisionless relativistic gas of gravitons, the fluid conservation equations are specifically given by [12, 13]$ \begin{eqnarray} \dot{\delta}_{\rm gw} + \frac{4}{3}\theta_{\rm gw} + \frac{2}{3}\dot{h} &=& 0\, , \end{eqnarray} $

(1) $ \begin{eqnarray} \dot{\theta}_{\rm gw} -\frac{1}{4}k^{2}\left(\delta_{\rm gw}-4\sigma_{\rm gw}\right) &=& 0\, , \end{eqnarray} $

(2) $ \begin{eqnarray} \dot{\sigma}_{\rm gw} - \frac{2}{15}\left(2\theta_{\rm gw}+\dot{h}+6\dot{\eta}\right) &=& 0\, , \end{eqnarray} $

(3) where h and η stand for the scalar metric perturbations in the corresponding gauge, k is the wavenumber of perturbations, and the overdot denotes the derivative with respect to the conformal time τ. They are identical in form to those for massless neutrinos [12]. This equivalence underpins the use of cosmological observational data to constrain

$ \Omega_{\rm gw} $ , with the phenomenology determined by the choice of initial conditions [12, 13].Initial conditions should be considered when resolving the above equations. For linear cosmological perturbations, Ref. [2] investigated adiabatic initial conditions, while Ref. [3] explored non-adiabatic initial conditions, as explicitly demonstrated in Table 1. Under the former assumption, all matter components share identical fractional energy-density perturbations, allowing tensor perturbations to be treated equivalently to massless neutrino perturbations. This implies that the effect of gravitational waves is equivalent to that of the effective neutrino number, denoted by

$ N_{\rm eff} $ . In contrast, under the latter non-adiabatic hypothesis, the cosmological gravitational-wave background exhibits no linear perturbations initially. Consequently, within the conformal Newtonian gauge, its energy-density perturbation must vanish. This is a distinct departure from the initial conditions for massless neutrinos, implying that the effect of gravitational waves cannot be absorbed into$ N_{\rm eff} $ .Adiabatic I.C. Homogeneous I.C. h $ \frac{1}{2} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ \frac{1}{2} k^2 \tau^2 $ η $ 1-\frac{\left(9-4 R_\gamma\right)}{12\left(19-4 R_\gamma\right)} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ 1-\frac{\left(9-4 R_\gamma+4 R_{\mathrm{gw}}\right)}{12\left(19-4 R_\gamma+4 R_{\mathrm{gw}}\right)} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ \delta_\gamma $ $ -\frac{1}{3} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ -\frac{R_{\mathrm{gw}}}{R_\gamma} \frac{20}{\left(19-4 R_\gamma+4 R_{\mathrm{gw}}\right)} $ $ \theta_\gamma $ $ \mathcal{O}\left(k^4 \tau^3\right) $ $ -\frac{R_{\mathrm{gw}}}{R_\gamma} \frac{5}{19-4 R_\gamma+4 R_{\mathrm{gw}}} k^2 \tau $ $ \delta_\nu $ $ -\frac{1}{3} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ -\frac{1}{3} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ \theta_\nu $ $ \mathcal{O}\left(k^4 \tau^3\right) $ $ \mathcal{O}\left(k^4 \tau^3\right) $ $ \sigma_\nu $ $ \frac{2}{3\left(19-4 R_\gamma\right)} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ \frac{2}{3\left(19-4 R_\gamma+4 R_{\mathrm{gw}}\right)} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ \delta_{\mathrm{gw}} $ $ -\frac{1}{3} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ \frac{20}{19-4 R_\gamma+4 R_{\mathrm{gw}}} $ $ \theta_{\mathrm{gw}} $ $ \mathcal{O}\left(k^4 \tau^3\right) $ $ \frac{5}{19-4 R_\gamma+4 R_{\mathrm{gw}}} k^2 \tau $ $ \sigma_{\mathrm{gw}} $ $ \frac{2}{3\left(19-4 R_\gamma\right)} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ \frac{4}{3\left(19-4 R_\gamma+4 R_{\mathrm{gw}}\right)} k^2 \tau^2 $ $ \delta_{\mathrm{c}} $ $ -\frac{1}{4} k^2 \tau $ $ -\frac{1}{4} k^2 \tau $ $ \delta_{\mathrm{b}} $ $ -\frac{1}{4} k^2 \tau $ $ -\frac{R_\gamma\left(19-4 R_\gamma\right)+2 R_{\mathrm{gw}}\left(2 R_\gamma-5\right)}{4 R_\gamma(19-4 R_\gamma+4 R_{\mathrm{gw}})} k^2 \tau $ Table 1. Adiabatic and homogeneous initial conditions in the synchronous gauge, expanded to second order in

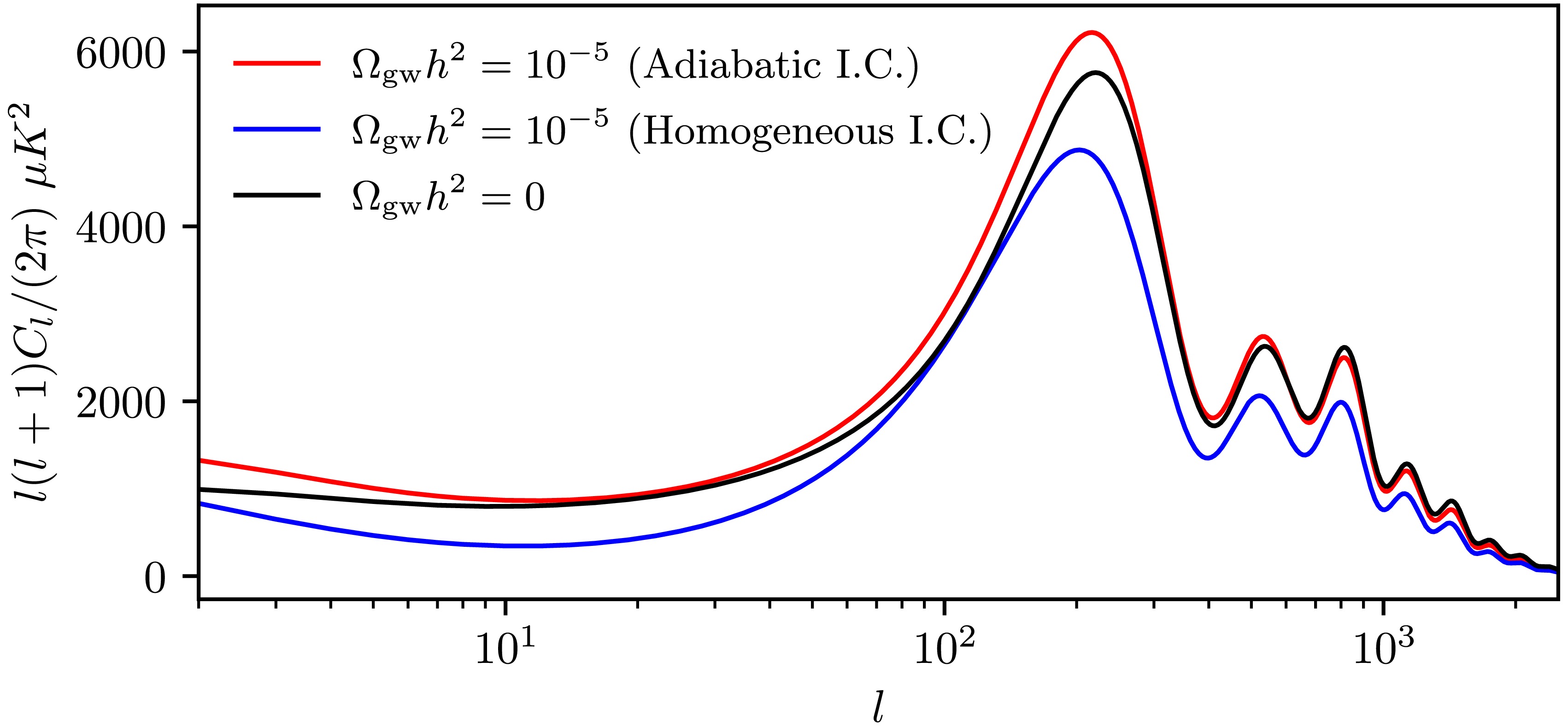

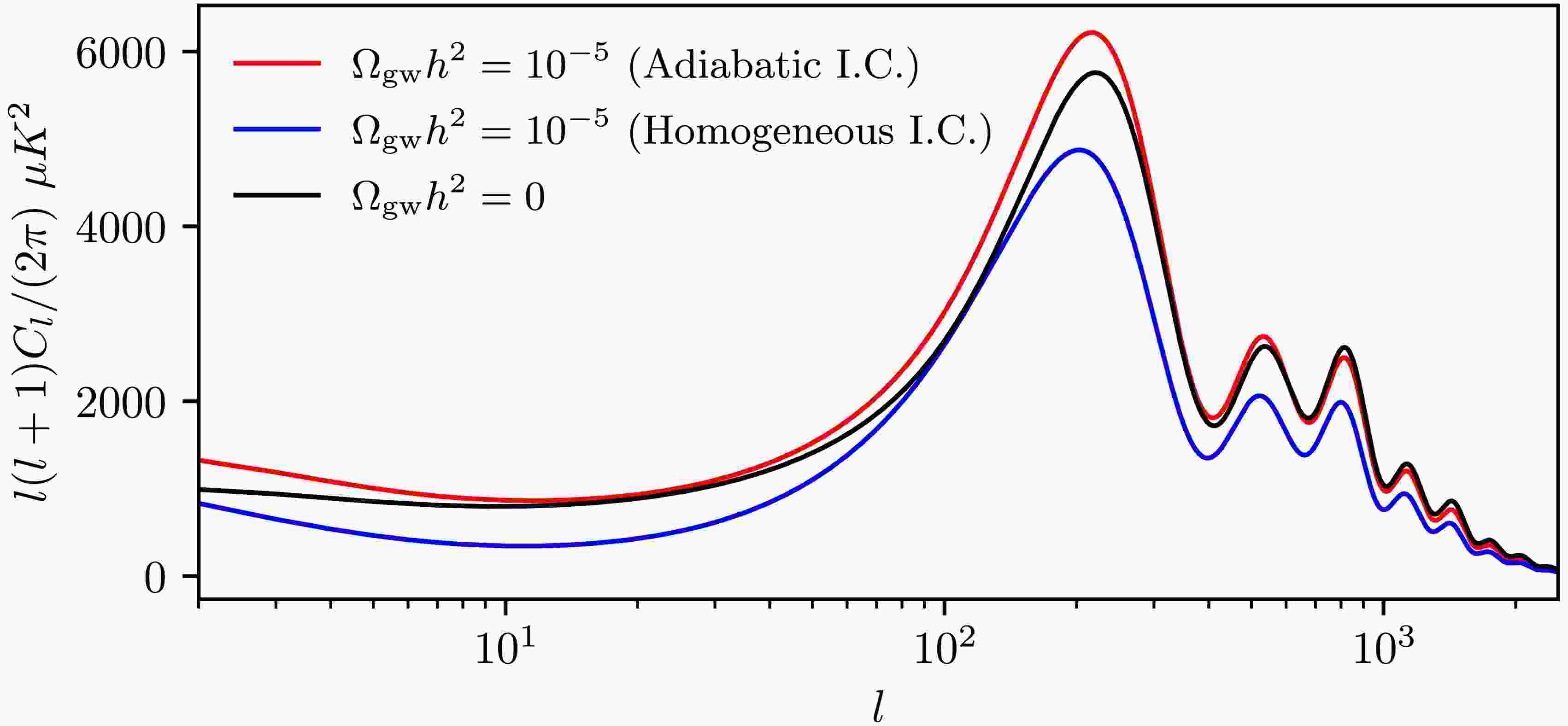

$ k\tau $ , are considered for the modes related to gravitational waves [13]. We define$ R_{i}=\rho_{i}/\sum\rho_{i} $ , where i represents γ, ν, or$ {\rm gw} $ . In this work,$ \delta_{i} $ ,$ \theta_{i} $ , and$ \sigma_{i} $ represent the density, velocity, and shear perturbations, respectively, in this gauge, with h and η denoting the metric perturbations.The initial conditions of tensor perturbations affect the observational constraints on the cosmological gravitational waves from CMB and BAO measurements, as demonstrated by Fig. 1. Gravitational waves in the short-wave approximation can contribute an additional radiative energy component, increasing the expansion rate of the early universe and postponing the epoch of matter-radiation equality. This, in turn, shifts the sound horizon at the time of recombination, thereby modifying the power of CMB perturbations on small scales. On the other hand, as shown in Eqs. (1), (3), gravitational-wave perturbations can influence the time derivatives of the scalar metric perturbations h and η. The latter, through the Einstein-Boltzmann equations, affects the evolution of photon and matter perturbations, thus leaving detectable imprints on the CMB angular power spectrum. If adiabatic initial conditions are assumed, the impact of these gravitational waves on CMB and BAO is identical to that of massless neutrinos. Consequently, existing CMB+BAO constraints on

$ N_{\rm eff} $ can be directly translated into constraints on the energy density of gravitational waves. In contrast, under non-adiabatic initial conditions, the gravitational-wave imprint diverges from that of massless neutrinos. By analyzing Planck 2018 CMB data and several BAO datasets, Ref. [13] derived upper limits (95% confidence level) on the energy-density fraction of gravitational waves, i.e.,$ \Omega_{\mathrm{gw}}h^{2}<1.7\times10^{-6} $ for adiabatic initial conditions and$ \Omega_{\mathrm{gw}}h^{2}<2.9\times10^{-7} $ for homogeneous initial conditions.

Figure 1. (color online) Effect of Adiabatic Versus Homogeneous Initial Conditions on the CMB Temperature Angular Power Spectrum. Here, we consider only the ΛCDM model for the sake of illustration.

In this work, we derive constraints on the cosmological gravitational-wave background from cutting-edge CMB and BAO observational data and evaluate the detection capabilities of next-generation CMB and BAO facilities. Accordingly, we have implemented the evolution equations and initial conditions for gravitational waves in the

$\mathrm{CLASS}$ [28] code. Specifically, within$\mathrm{CLASS}$ , we have replicated and adapted the code modules pertaining to massless neutrinos, adopting the initial conditions listed in Table 1 of Ref. [13] to enable the code for studying gravitational waves. We exclusively consider adiabatic and homogeneous initial conditions for gravitational waves, since isocurvature initial conditions are already tightly constrained by Planck [29].Having accounted for adiabatic and homogeneous initial conditions, we investigate the physical energy-density fraction of gravitational waves in both the standard cosmological model, i.e., the ΛCDM model, and its extension incorporating the Chevallier-Polarski-Linder (CPL) parametrization [30, 31] of the equation of state of dark energy. For the former case, we consider seven independent parameters:

$ 10^{6}\Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ ,$ \Omega_{b}h^{2} $ ,$ \Omega_{c}h^{2} $ ,$ 100\theta_{\rm MC} $ , τ,$ \ln(10^{10}A_{s}) $ , and$ n_{s} $ , with the pivot scale being$ k_{p}=0.05 $ $ {\rm Mpc}^{-1} $ . The physical definitions of these parameters align with those established in the Planck collaboration's paper [29]. For the latter scenario, the inclusion of the dark-energy equation of state$ w(a) = w_{0} + w_{a}(1-a) $ , with a being the scale factor of the universe, necessitates two additional independent parameters, specifically$ w_{0} $ and$ w_{a} $ . -

To constrain the model parameters, we jointly analyze the cutting-edge CMB and BAO observational datasets. For the former, we employ the CMB-SPA data combination, whose composition has been detailed in Table III of the SPT-3G collaboration's paper [32]. In brief, this refers to a data combination incorporating observations of CMB temperature anisotropies, polarization, and lensing from Planck, South Pole Telescope (SPT-3G), and Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) [33−36]. For the latter, we utilize the recent BAO data from DESI [23]. Here, we perform cosmological parameter inference using the Markov-Chain Monte-Carlo (MCMC) sampler in

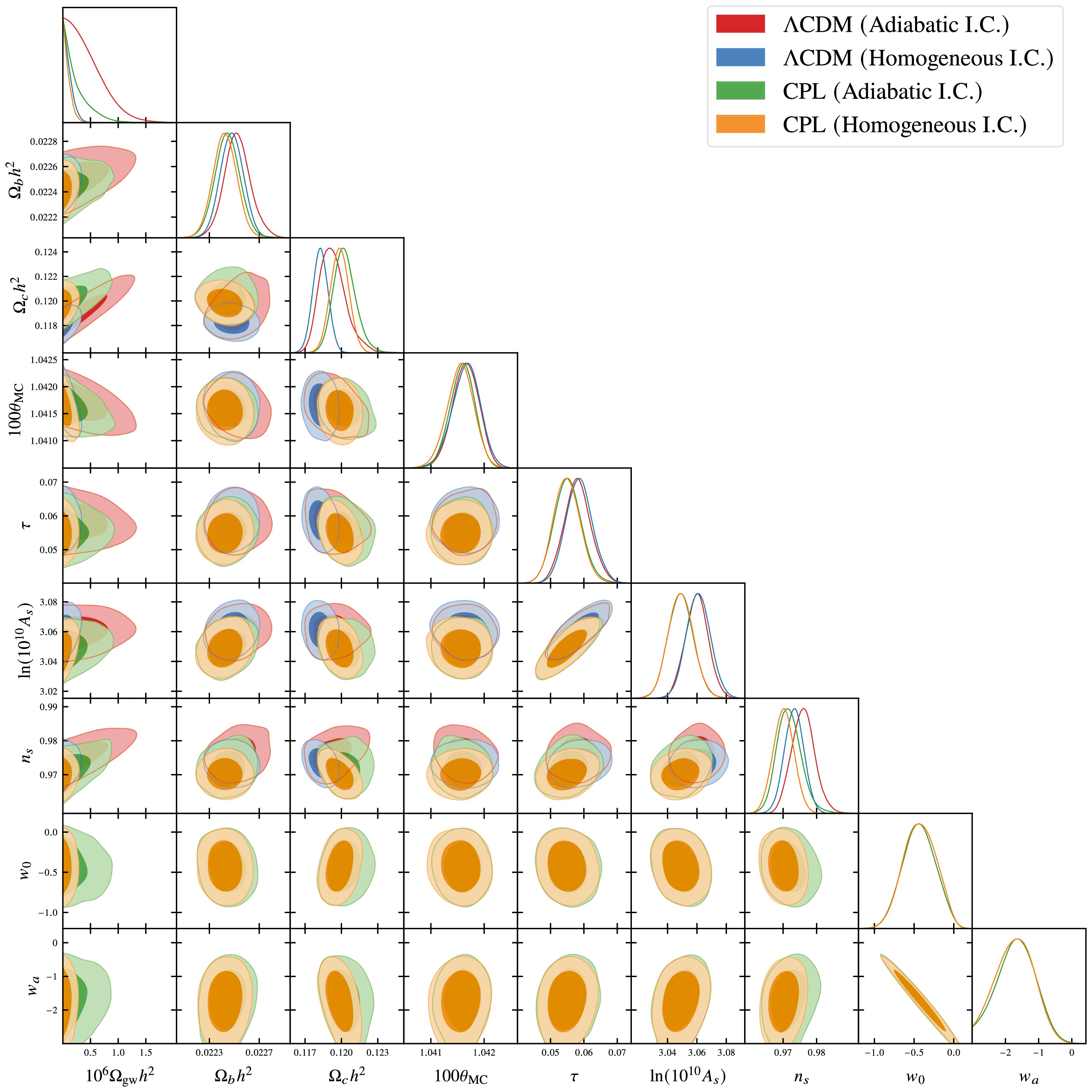

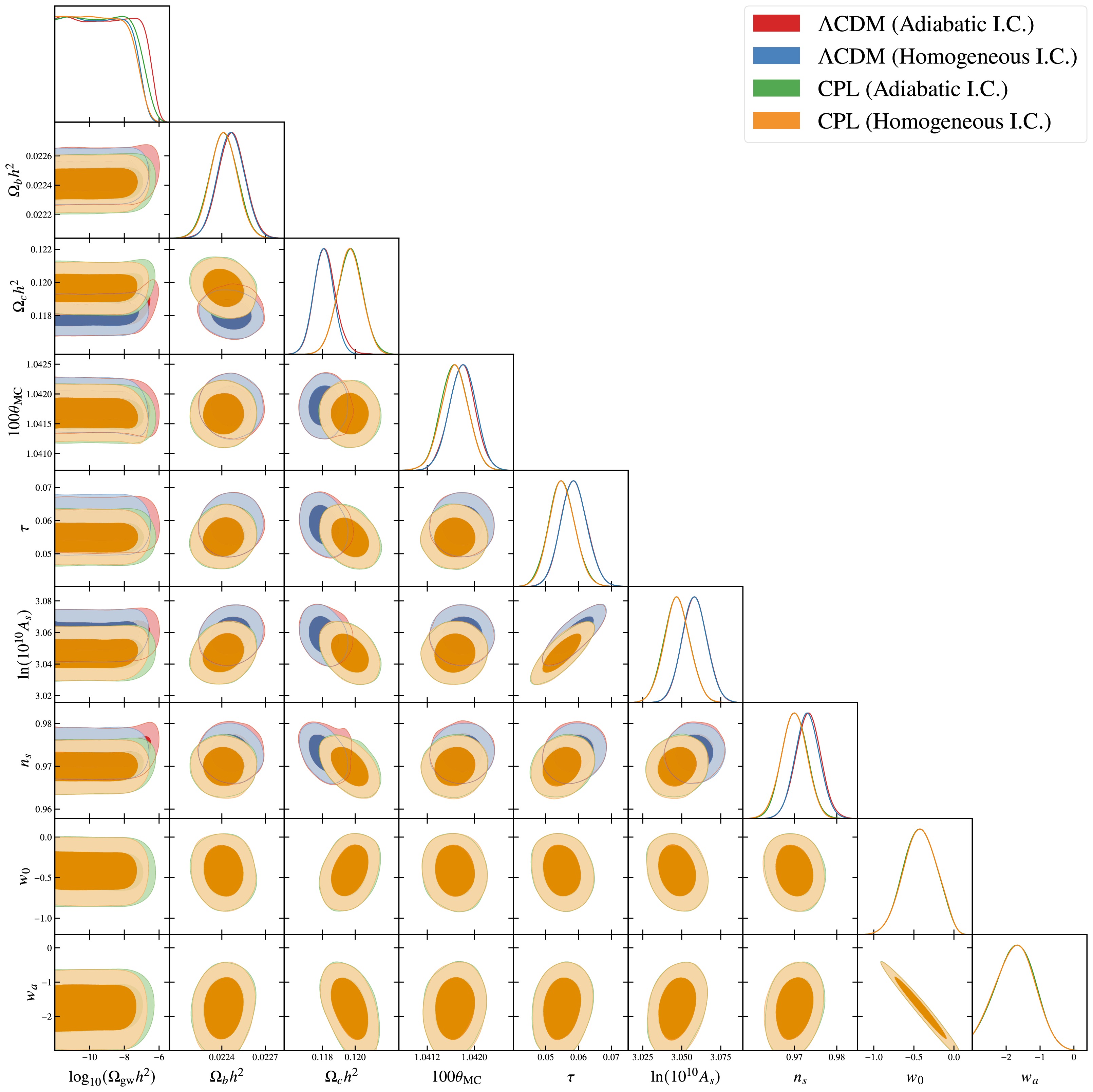

$\mathrm{cobaya}$ [37].The data analysis results are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2 for a uniform prior for

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ in the interval of$ 0<\Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<4\times10^{-6} $ , while in Table 3 and Fig. 3 for a log-uniform prior for$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ in the interval of$ 10^{-12}<\Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<4\times10^{-6} $ . In this work, the abbreviation I.C. denotes initial conditions for gravitational waves. Parameter uncertainties are quoted at the 68% confidence level in Tables 2 and 3, while upper limits on parameters are reported at the 95% confidence level. The one- and two-dimensional posterior distributions of these parameters are presented in Figs. 2 and 3.ΛCDM ΛCDM CPL CPL (Adiabatic I.C.) (Homogeneous I.C.) (Adiabatic I.C.) (Homogeneous I.C.) $ \Omega_{\mathrm{b}} h^2 $ $ 0.02253^{+ 0.00010}_{- 0.00011} $ $ 0.02248 \pm 0.00009 $ $ 0.02245 \pm 0.00010 $ $ 0.02242 \pm 0.00010 $ $ \Omega_{\mathrm{c}} h^2 $ $ 0.11930^{+ 0.00085}_{- 0.00120} $ $ 0.11827 \pm 0.00063 $ $ 0.12028^{+ 0.00080}_{- 0.00100} $ $ 0.11986 \pm 0.00076 $ $ 100 \theta_{ \rm{ \rm{MC}}} $ $ 1.04165 \pm 0.00025 $ $ 1.04166^{+ 0.00028}_{- 0.00024} $ $ 1.04159 \pm 0.00023 $ $ 1.04156 \pm 0.00025 $ τ $ 0.0581 \pm 0.0040 $ $ 0.0586 \pm 0.0040 $ $ 0.0552 \pm 0.0041 $ $ 0.0549 \pm 0.0039 $ $ \ln (10^{10} A_{\mathrm{s}}) $ $ 3.0599 \pm 0.0077 $ $ 3.0610 \pm 0.0081 $ $ 3.0490 \pm 0.0086 $ $ 3.0491 \pm 0.0085 $ $ n_{\mathrm{s}} $ $ 0.9760 \pm 0.0035 $ $ 0.9733 \pm 0.0029 $ $ 0.9718^{+ 0.0032}_{- 0.0039} $ $ 0.9702 \pm 0.0031 $ $ w_0 $ $ -1 $ (fixed)$ -1 $ (fixed)$ - 0.44 \pm 0.20 $ $ - 0.43 \pm 0.20 $ $ w_a $ $ 0 $ (fixed)$ 0 $ (fixed)$ - 1.67 \pm 0.57 $ $ - 1.71 \pm 0.57 $ $ 10^6 \Omega_{\mathrm{gw}} h^2 $ $< 1.04 $ $< 0.27 $ $< 0.72 $ $< 0.24 $

Figure 2. (color online) Same as Table 2, but we depict the one- and two-dimensional posterior distributions of the parameters. The dark and light shaded regions denote the 68% and 95% confidence intervals, respectively.

ΛCDM ΛCDM CPL CPL (Adiabatic I.C.) (Homogeneous I.C.) (Adiabatic I.C.) (Homogeneous I.C.) $ \Omega_{\mathrm{b}} h^2 $ $ 0.02247 \pm 0.00009 $ $ 0.02246 \pm 0.00009 $ $ 0.02241 \pm 0.00010 $ $ 0.02241 \pm 0.00009 $ $ \Omega_{\mathrm{c}} h^2 $ $ 0.11816^{+ 0.00059}_{- 0.00070} $ $ 0.11807 \pm 0.00060 $ $ 0.11969 \pm 0.00077 $ $ 0.11967 \pm 0.00075 $ $ 100 \theta_{\text{MC}} $ $ 1.04179 \pm 0.00022 $ $ 1.04180 \pm 0.00023 $ $ 1.04166 \pm 0.00023 $ $ 1.04167 \pm 0.00023 $ τ $ 0.0586 \pm 0.0040 $ $ 0.0586 \pm 0.0040 $ $ 0.0549 \pm 0.0040 $ $ 0.0550 \pm 0.0039 $ $ \ln (10^{10} A_{\mathrm{s}}) $ $ 3.0583 \pm 0.0079 $ $ 3.0581 \pm 0.0079 $ $ 3.0469 \pm 0.0082 $ $ 3.0470 \pm 0.0082 $ $ n_{\mathrm{s}} $ $ 0.9732 \pm 0.0030 $ $ 0.9730 \pm 0.0029 $ $ 0.9701 \pm 0.0030 $ $ 0.9699 \pm 0.0030 $ $ w_0 $ $ - 1 $ (fixed)$ - 1 $ (fixed)$ - 0.42 \pm 0.20 $ $ - 0.42 \pm 0.20 $ $ w_a $ $ 0 $ (fixed)$ 0 $ (fixed)$ - 1.72 \pm 0.56 $ $ - 1.73 \pm 0.56 $ $ 10^6 \Omega_{\mathrm{gw}} h^2 $ $< 0.28 $ $< 0.07 $ $< 0.13 $ $< 0.06 $ Table 3. The text provided does not contain any grammatical errors. However, here is a slightly refined version to enhance clarity and conciseness: Same as Table 2, but using the log-uniform prior for

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ within the interval$ 10^{-12}<\Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<4\times10^{-6} $ .

Figure 3. (color online) The text is correctly written and does not require any changes: Same as Table 3, but we depict one- and two-dimensional posterior distributions of parameters. The dark and light shaded regions denote 68% and 95% confidence intervals, respectively.

Based on Table 2, we find that the addition of dynamical dark energy suppresses the observational upper bounds on

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ , with the degree of suppression depending on the chosen initial conditions for gravitational waves. Under adiabatic initial conditions, the upper limits are$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<1.0\times10^{-6} $ (ΛCDM) and$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<7.2\times10^{-7} $ (CPL), revealing a difference of$ \sim $ 30%. For homogeneous initial conditions, they become$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<2.7\times10^{-7} $ (ΛCDM) and$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<2.4\times10^{-7} $ (CPL), revealing a difference of$ \sim $ 10%. However, these results indicate that the constraints on$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ under homogeneous initial conditions are less sensitive to the choice of dark energy model. This is also reflected in the one-dimensional posterior distributions of$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ , as shown in the top subfigure of Fig. 2. Furthermore, we find that for the ΛCDM model, the upper limits obtained here are tighter by at most 40% than those reported in existing literature [13]. This improvement is primarily attributable to our employment of state-of-the-art observational datasets.A comparison between the results in Table 3 and Table 2 reveals that our cosmological constraints on cosmological gravitational waves exhibit a non-negligible dependence on the choice of parameter prior. The bounds derived under a log-uniform prior are more stringent by a factor of

$ \sim4 $ than those obtained using a uniform prior. Specifically, under adiabatic initial conditions, the upper limits are given by$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<2.8\times10^{-7} $ (ΛCDM) and$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<1.3\times10^{-7} $ (CPL), while for homogeneous initial conditions, they become$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<0.7\times10^{-7} $ (ΛCDM) and$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<0.6\times10^{-7} $ (CPL). Since$ \Omega_{\rm gw} $ can span several orders of magnitude, a log-uniform prior provides a more natural and less informative sampling across this broad range. Consequently, it more effectively constrains the parameter's extreme values. This comparison indicates that while the numerical results are prior-sensitive, the stricter constraints derived under the log-uniform prior represent a more robust and physically credible conclusion of our analysis.We further find that homogeneous initial conditions yield more stringent observational constraints on

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ compared to adiabatic initial conditions. This could be attributed to the fact that while adiabatic gravitational waves enhance the total power of cosmological perturbations, their homogeneous counterparts suppress it, as demonstrated in Fig. 1. Physically, under homogeneous initial conditions, gravitational-wave perturbations and photon perturbations evolve out of phase within the horizon due to their initial conditions having opposite signs. -

The aforementioned findings can be rigorously tested by future cosmological observational data and are expected to enable more precise measurements of the cosmological gravitational-wave background. As a next-generation flagship spectroscopic survey, CSST [27] is expected to obtain slitless spectroscopic data from numerous galaxies and AGNs, potentially delivering enhanced measurements of BAO across multiple redshift bins, thereby providing deeper insights into the nature of dark energy. Furthermore, a joint analysis of CSST's BAO measurements with the CMB observational data from next-generation experiments such as LiteBIRD [25] and S4 [26] could achieve higher-precision constraints on cosmological parameters, particularly including

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ .By utilizing the MCMC sampler in the

$\mathrm{MontePython}$ [38, 39] code, we analyze the combination of BAO data from CSST and CMB data from LiteBIRD and S4 to determine the projected precision of$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ measurements from this experimental configuration. For the former, we adopt the pessimistic precision of CSST BAO measurements from Table 3 in Ref. [40], representing a conservative projection. We integrate this dataset with its likelihood into$\mathrm{MontePython}$ by calibrating the dataset to align with our fiducial models. For the latter, we follow the methodology of Ref. [38], i.e., using LiteBIRD's projected precision for data at large angular scales while adopting S4's projected precision for data at small angular scales. Specifically, we employ the mock likelihoods$\mathrm{litebird}\_\mathrm{lowl}$ , integrating measurements of temperature anisotropies and polarization at$ 2\leq\ell\leq50 $ , and$\mathrm{cmb}\_\mathrm{s4}\_\mathrm{highl}$ , integrating measurements of temperature anisotropies, polarization, and lensing at$ \ell>50 $ . As an approximation, we neglect potential correlations between CMB and BAO measurements. Furthermore, each fiducial model is determined by the upper-limit value of$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ and the central values of other parameters provided in Table 2. Here, we still assume a uniform prior for this parameter in order to perform a conservative estimate.The data analysis reveals that the combined dataset is projected to detect deviations of

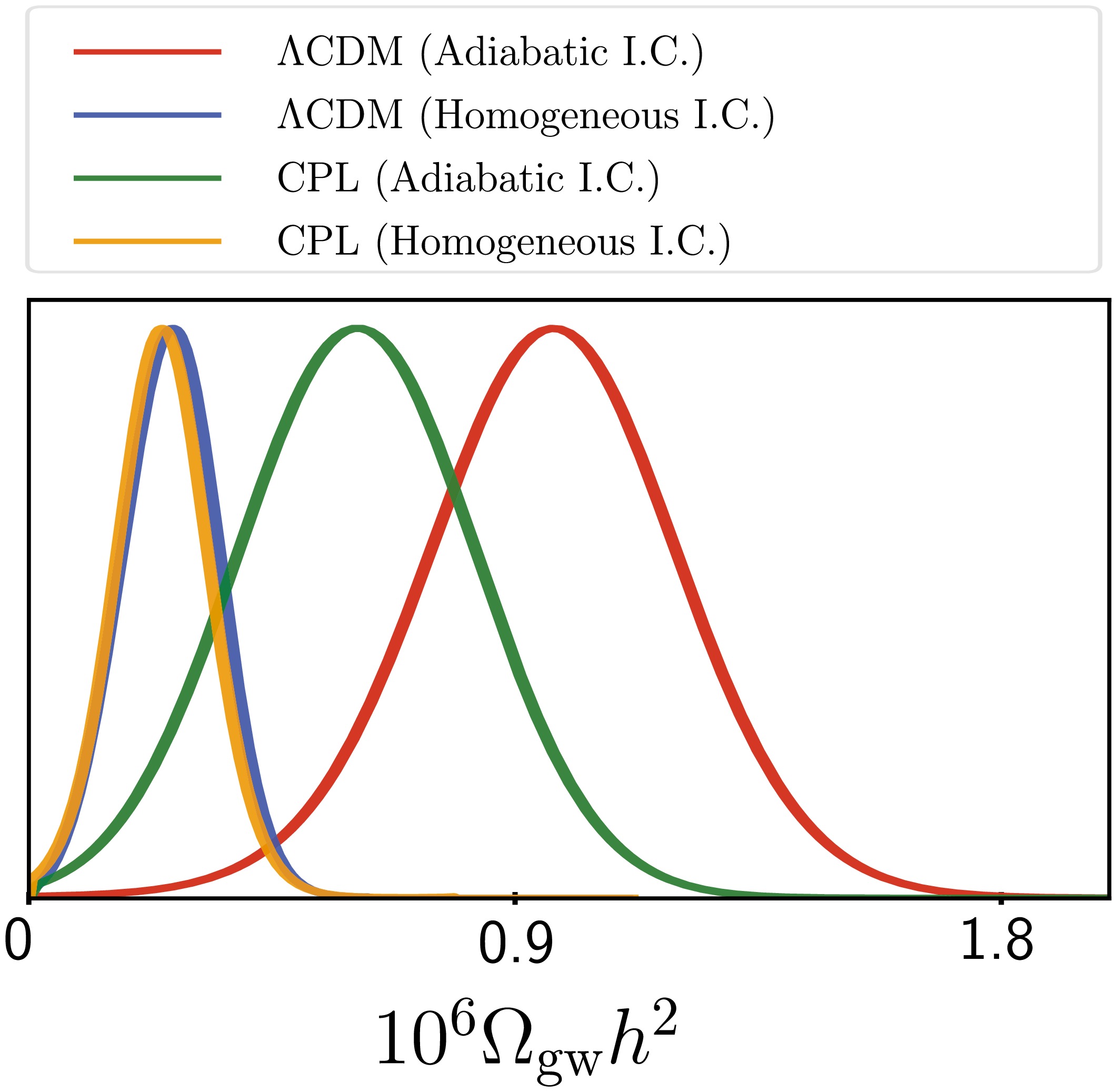

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ from zero at the$ \sim2.5-4\sigma $ confidence level; otherwise, it is expected to further tighten the observational upper limits on$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ . Under adiabatic initial conditions, the projected results (68% confidence interval) are$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}=1.04_{-0.25}^{+0.24}\times10^{-6} $ (ΛCDM) and$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}=7.2_{-2.5}^{+2.3}\times10^{-7} $ (CPL), with the measurement precisions being almost the same. For homogeneous initial conditions, they become$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}=2.7_{-1.0}^{+0.9}\times10^{-7} $ (ΛCDM) and$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}=2.4_{-1.0}^{+0.9}\times10^{-7} $ (CPL), with the measurement precisions also being the same. Correspondingly, the one-dimensional posterior distributions of this parameter are presented in Fig. 4, which allows for direct comparison with the top subfigure of Fig. 2.

Figure 4. (color online) The one-dimensional posterior distributions of

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ are obtained from the data combination of CSST [27], LiteBIRD [25], and S4 [26]. Each fiducial model is determined by the upper-limit value of$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ and the central values of other parameters provided in Table 2.It is particularly intriguing that across both the ΛCDM and CPL cosmological frameworks, the projected precision for measuring

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ with future detection facilities registers at$ \sigma \simeq 2.5 \times 10^{-7} $ (and$ 2\sigma \simeq 4.8 \times 10^{-7} $ ) under adiabatic initial conditions and$ \sigma \simeq 1.0 \times 10^{-7} $ (and$ 2\sigma \simeq 1.8 \times 10^{-7} $ ) under homogeneous initial conditions, respectively, revealing model-independent enhancement prospects. Such precision enhancements stem from the deployment of more sensitive next-generation instrumentation, surpassing current measurement capabilities. Furthermore, consistent with the analysis shown in the last section, homogeneous initial conditions still produce tighter observational constraints on$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ than adiabatic initial conditions. -

In this study, we have derived new constraints on the present-day physical energy-density fraction of cosmological gravitational waves through joint analysis of the data combination of CMB from Planck, ACT, and SPT-3G and BAO from DESI. As presented in Table 2, under physically motivated homogeneous initial conditions for tensor perturbations, the constraints at the 95% confidence level were measured as

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<2.7\times10^{-7} $ in the ΛCDM model and$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}<2.4\times10^{-7} $ in the CPL model, respectively. However, under adiabatic initial conditions, these constraints became less stringent. Furthermore, the choice of priors for$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ can change the results of our present work to some extent. For the aforementioned upper limits, we have used the uniform prior for$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2}>0 $ . In contrast, if we used the log-uniform prior, the upper limits, as presented in Table 3, would become smaller by a factor of 4, leading to more stringent constraints.When jointly analyzing CMB and BAO data, we should notice potential residual systematics that may not have been fully eliminated, as well as possible correlations between CMB and BAO measurements. For the CMB anisotropies and polarization, correlations between Planck and ACT are controlled via the multipole cuts, while SPT-3G is effectively independent of Planck and ACT, given minimal sky overlap [36]. For the CMB lensing, correlations between ACT and SPT-3G have been shown negligible for cosmological parameter estimation [32]. For the BAO distances, DESI DR2 has propagated a quantified systematics budget in the covariance and demonstrated that strong correlations between redshift-bin systematics have no detectable impact on cosmological constraints [23]. Furthermore, CMB and BAO are typically modeled to be independent in joint fits. Ref. [41] has also shown that cross-correlations between CMB and BAO induce only small corrections for most parameters, so neglecting such cross-correlations is a well-justified approximation. Therefore, we expect the results of our present work to remain robust.

We have further derived projected constraints on

$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ by analyzing the combined CMB data from LiteBIRD and S4 alongside BAO data from CSST. These next-generation facilities were anticipated to improve current observational bounds on$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ due to their enhanced detection capabilities. We revealed that homogeneous initial conditions deliver enhanced measurement precision for$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ compared to adiabatic initial conditions, while the specific nature of dark energy exerts no discernible influence on the precision. If we still used a uniform prior of$ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $ as a conservative estimate, the measurement precision was shown as$ \sigma\simeq2.5\times10^{-7} $ (and$ 2\sigma\simeq4.8\times10^{-7} $ ) under adiabatic initial conditions and$ \sigma\simeq1.0\times10^{-7} $ (and$ 2\sigma\simeq1.8\times10^{-7} $ ) under homogeneous initial conditions, respectively.In this work, we have aimed to establish model-agnostic constraints on the cosmological gravitational-wave background. Consequently, we did not focus on specific scenarios of cosmological gravitational waves. The constraints obtained here could provide critical benchmarks for exploring the cosmological origins of gravitational waves within the frequency band

$ f \gtrsim 10^{-15} $ Hz and potentially enable joint analysis with direct gravitational-wave detection sensitive to this regime. For example, recent data from PTAs have provided strong evidence for a stochastic gravitational-wave background in the nanohertz frequency range [5−8]. If this signal originates from cosmological sources, such as induced gravitational waves, its infrared (IR) spectral behavior could offer a viable explanation (see, e.g., Ref. [42]). The constraints derived in this work, while less direct than PTA measurements in the nHz band, offer a complementary probe. PTAs measure the spectral energy density at nanohertz frequencies, whereas our cosmological analysis is sensitive to the total energy density integrated over a much broader frequency range. This complementarity means that, in principle, the combination of cosmological and PTA data can break degeneracies and provide significantly tighter constraints on models of the cosmological gravitational-wave background [17−19]. Should the need arise, we can combine the cosmological constraints with direct gravitational-wave detection data for in-depth model investigations. However, we would like to designate such research for future works.

New constraints on cosmological gravitational waves from CMB and BAO in light of dynamical dark energy

- Received Date: 2025-08-13

- Available Online: 2026-02-15

Abstract: In this work, we derive upper limits on the physical energy-density fraction today of cosmological gravitational waves, denoted by $ \Omega_{\rm{gw}}h^{2} $, by analyzing Planck, ACT, SPT CMB, and DESI BAO data combinations. In the standard cosmological model, we establish 95% CL upper limits of $ \Omega_{\rm{gw}}h^{2} < 1.0 \times 10^{-6} $ for adiabatic initial conditions and $ \Omega_{\rm{gw}}h^{2} < 2.7 \times 10^{-7} $ for homogeneous initial conditions, assuming a uniform prior for $ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $. In light of dynamical dark energy, we obtain $ \Omega_{\rm{gw}}h^{2} < 7.2 \times 10^{-7} $ (adiabatic) and $ \Omega_{\rm{gw}}h^{2} < 2.4 \times 10^{-7} $ (homogeneous). In contrast, if a log-uniform prior is assumed for $ \Omega_{\rm gw}h^{2} $, these constraints become tighter by a factor of approximately 4, suggesting the results are prior-sensitive. Furthermore, we project the sensitivity achievable with LiteBIRD and CMB Stage-IV measurements of CMB and CSST observations of BAO, forecasting 68% CL uncertainties of $ \sigma = 2.5 \times 10^{-7} $ (adiabatic) and $ \sigma = 1.0 \times 10^{-7} $ (homogeneous) for $ {\Omega_{\rm{gw}}h^{2}} $. The constraints obtained in this work provide critical benchmarks for exploring the cosmological origins of gravitational waves within the frequency band $ f \gtrsim 10^{-15} $ Hz and potentially enable joint analysis with direct gravitational-wave detection sensitive to this regime.

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: