-

The lowest-lying resonance in QCD is the broad

$ \sigma $ -meson (also called$ f_0(500) $ ), with its parameters precisely determined from various dispersion-theoretical analyses of pion-pion scattering, see e.g. [1, 2]. Still, due to its large width, the$ \sigma $ (and other scalar mesons) plays a rather different role in the low-energy effective field theory of QCD than the vector or axial-vector mesons. The latter clearly saturate the low-energy constants to which they can contribute, as known since long [3, 4]. In the scalar sector, the heavier mesons like the$ f_0(980) $ and$ a_0(980) $ are considered in the studies of resonance saturation, but their contribution to the low-energy constants is small, except for$ L_5 $ and$ L_8 $ , which, however, are used to fix certain scalar couplings [3]. Later, it was argued in Ref. [5] that the imaginary part of the pion scalar form factor can be understood in terms of a broad scalar meson, building upon the detailed investigations in [6, 7]. Further, in Ref. [8] it was shown that the dimension-two low-energy constant$ c_1 $ , that parametrizes the leading explicit chiral symmetry breaking in the effective pion-nucleon Lagrangian, can be saturated by scalar meson exchange for a particular value of the ratio$ M_{\sigma}/g_{\sigma NN} $ , with$ M_{\sigma} $ the mass of the$ \sigma $ and$ g_{\sigma NN} $ the coupling of the$ \sigma $ to nucleons. Note that in the two-nucleon system the$ \sigma $ -meson essentially parametrizes the nuclear binding (in the one-boson-exchange approximation). In fact, for some particular boson-exchange model, this ratio is close to the one required by resonance exchange saturation. For details, the reader is referred to Ref. [8].In this note, we want to reconsider the

$ \sigma $ -meson contribution to the scalar form factors of the pion and the nucleon in a chiral perturbation theory calculation at one loop, where the effective Lagrangian is supplemented by an explicit broad scalar meson. A comparison with the existing precision calculations of these form factors will allow us to draw a conclusion about the role of the$ f_0(500) $ in the context of resonance saturation. We also note that our approach is not the scale-chiral perturbation theory proposed in Ref. [9], which considers the broken conformal symmetry of QCD. The effective Lagrangian approach to that phenomenon was originally developed in Refs. [10, 11].The paper is organized as follows: In Sec. 2 we give the basic definitions of the scalar form factors under investigation. Then, in Sec. 3 we calculate the imaginary part of the pion scalar form factor and compare with the precise determination based on dispersion theory. Sec. 4 contains the analogous calculation of the nucleon scalar form factor and the comparison with the corresponding nucleon spectral function at two loops in heavy baryon chiral perturbation theory. We end with a short summary.

-

The scalar form factor of the pion and the nucleon are defined via the matrix element of the scalar quark density

$ \bar{q}q $ in the isospin symmetry limit$ \begin{split} F_{\pi}^{S}(t) = &\;\left\langle {\pi(p_{f})|\hat{m}(\bar{u}u+\bar{d}d)|\pi(p_i)} \right\rangle\; ,\\ \sigma(t) =& \;\frac{1}{2m_N}\left\langle {N(p_{f})|\hat{m}(\bar{u}u+\bar{d}d)|N(p_i)} \right\rangle, \end{split} $

(1) with

$ t = (p_f-p_i)^2 $ the invariant momentum transfer squared,$ m_N $ the nucleon mass and$ \hat{m} = (m_u+m_d)/2 $ the average light quark mass. The scalar form factor of the nucleon satisfies the once-subtracted dispersion relation$ \sigma(t)\; = \;\sigma_{\pi N}+\frac{t}{\pi} \int_{t_0}^{\infty} {\rm d}t'\frac{{\rm Im} \sigma(t')}{t'(t'-t)} $

(2) where

$ t_0 $ is the threshold energy for hadronic intermediate states. The$ \pi N $ $ \sigma $ -term$ \sigma_{\pi N} = \sigma(0) $ is defined via the Feynman-Hellman theorem at t = 0, similar to the form factor$ F_{\pi}^S $ , which gives the pion$ \sigma $ -term at zero momentum transfer. It is known that$ F_{\pi}^S (0) = (0.99\pm 0.02)M_{\pi}^2 $ [7], so in what follows we consider the normalized scalar pion form factor$ F_{\pi}^S (t)/M_{\pi}^2 $ . Here,$ M_{\pi} $ denotes the charged pion mass. In this paper, we want to investigate the$ \sigma $ -meson contribution to these scalar form factors and draw some conclusion on the related issue of scalar meson dominance. -

In this section, we want to calculate the imaginary part of the scalar pion form factor with a particular emphasis on the contribution from the broad

$ \sigma $ -meson, cf. Fig. 1(a). For definiteness, we use

Figure 1. σ-meson contribution to the isoscalar scalar form factors of the pion (a) and the nucleon (b, c). Dashed and solid lines denote pions and nucleons, respectively. The double dashed lines and the cross represent the σ-meson and the scalar source, respectively. The light dots represent leading order vertices while the heavy dot characterizes a dimension-two pion-nucleon vertex.

$ M_{\sigma} = 478~ {\rm MeV}\; ,\; \; \; \; \Gamma_{\sigma} = 324~ {\rm MeV}\; \; . $

(3) Further, we adopt the choice in [12] for

$ \sigma $ -propagator,$ S_{\sigma}(t) = \frac{1}{t-M_{\sigma}^2+i\Gamma_{\sigma}(t)M_{\sigma}} $

where the co-moving width

$ \Gamma_{\sigma}(t) $ is given by$ \Gamma_{\sigma}(t) = \Gamma_{\sigma}\frac{M_{\sigma}}{\sqrt{t}}\frac{\sqrt{t/4-M_{\pi}^2}}{\sqrt{M_{\sigma}^2/4-M_{\pi}^2}} $

(4) with momentum transfer squared t, see also the discussion in Ref. [13].

The following power counting rules for the loop diagrams are used (we consider here the pion and the nucleon case together to keep the presentation compact): vertices from

$ {\cal L}^{(n)} $ count as$ {\cal O}(q^n) $ , so we count the nucleon propagator as$ {\cal O}(q^{-1}) $ , and the sigma and pion propagators as$ {\cal O}(q^{-2}) $ . Thus the chiral order of the diagram in Fig. 1(a) is$ {\cal O}(q^3) $ , as only lowest order vertices from$ {\cal L}^{(2)}_{\pi\pi} $ are involved, and the diagrams in Fig. 1(b)-(c) are$ {\cal O}(q^4) $ at low energies, i.e. for small t (for precise definitions of the pion-nucleon Lagrangian, see Sec. 4).Let us briefly discuss the kinematics for evaluating the diagrams shown in Fig. 1. We start with the nucleon case, as it is more general. We work in the center-of-momentum frame of the nucleon pair with

$ q = \big(-2E_p,\; \vec{0}\,\big) $ . The initial and the final momentum of the nucleons are, respectively,$ p_i = \big(E_p,\; \vec{p}\,\big) $ ,$ p_f = \big(-E_p,\; \vec{p}\,\big) $ , with$ |\vec{p}\,| = (t/4 - m_N^2)^{1/2} $ and$ E_p = (m_N^2+|\vec{p}\,|^2)^{1/2} $ . The imaginary part of the loop diagram corresponds to a cut diagram for the momentum transfer squared$ t \geq 4M_{\pi}^2 $ . For this calculation, we perform a reduction to scalar loop integrals and thus require the basic scalar loop integrals of one- and two- point functions, respectively,$ \begin{split}A_0(m^2) =& \frac{(2 \pi \mu)^{4-n}}{i \pi^2}\int \frac{{\rm d}^nk}{k^2-{m}^2+i\epsilon^+}, \\ B_0(q^2, m_1^2, m_2^2) =& \frac{(2 \pi \mu)^{4-n}}{i \pi^2}\! \int\! \frac{{\rm d}^nk}{[k^2\!-\!m_1^2 \!+\!i\epsilon^+][(k\!+\!q)^2\!-\!m_2^2\!+\!i\epsilon^+]} \end{split}$

(5) with

$ q^2 = t = (p_f-p_i) $ and$ \epsilon^+ $ stands for$ \epsilon \to 0^+ $ . For the pion case, we need to consider these functions with$ m = m_1 = m_2 = M_{\pi} $ and the corresponding kinematical variables are simply obtained by the substitution$ m_N \to M_{\pi} $ in the above-mentioned formulas.The one-loop contribution depicted in Fig. 1(a) is readily evaluated

$ \begin{split} {\rm Im}\; F_{\pi}^S(t)\;= \frac{B g_{\sigma} g_{\sigma \pi \pi} \Big(A_0(M_{\pi}^2)(12 t-14 M_{\pi}^2)+(15M_{\pi}^2 t-6M_{\pi}^4-6t^2 )\, {\rm Re}[{B_0(t, M_{\pi}^2, M_{\pi}^2)}]\Big)}{3F_{\pi}^4 \pi^2} \times \frac{-M_{\sigma} \Gamma_{\sigma}(t) }{t^2+M_{\sigma}^4-2 M_{\sigma}^2 t + M_{\sigma}^2 \Gamma_{\sigma}^2 (t) } \end{split}$

(6) where

$ \begin{split}& A_0(m^2) = -2 m^2 \log\Big(\frac{m}{\mu}\Big), \\ & B_0(t,m_1^2,m_2^2) = 1-2 \log\Big(\frac{m_{1}}{{\mu}}\Big)-\frac{(t-m_1^2+m_2^2)\log\Big(\displaystyle\frac{m_{2}}{{m_1}}\Big)}{t} \\ &\quad - \frac{2m_1 m_2 \sqrt{1-\displaystyle\frac{(m_1^2+m_2^2-t)^2}{4m_1^2 m_2^2}} {\rm arccos} \Big[\displaystyle\frac{m_1^2+m_2^2-t}{2 m_1 m_2}\Big]}{t}. \end{split} $

The following values for the various masses and couplings constants are:

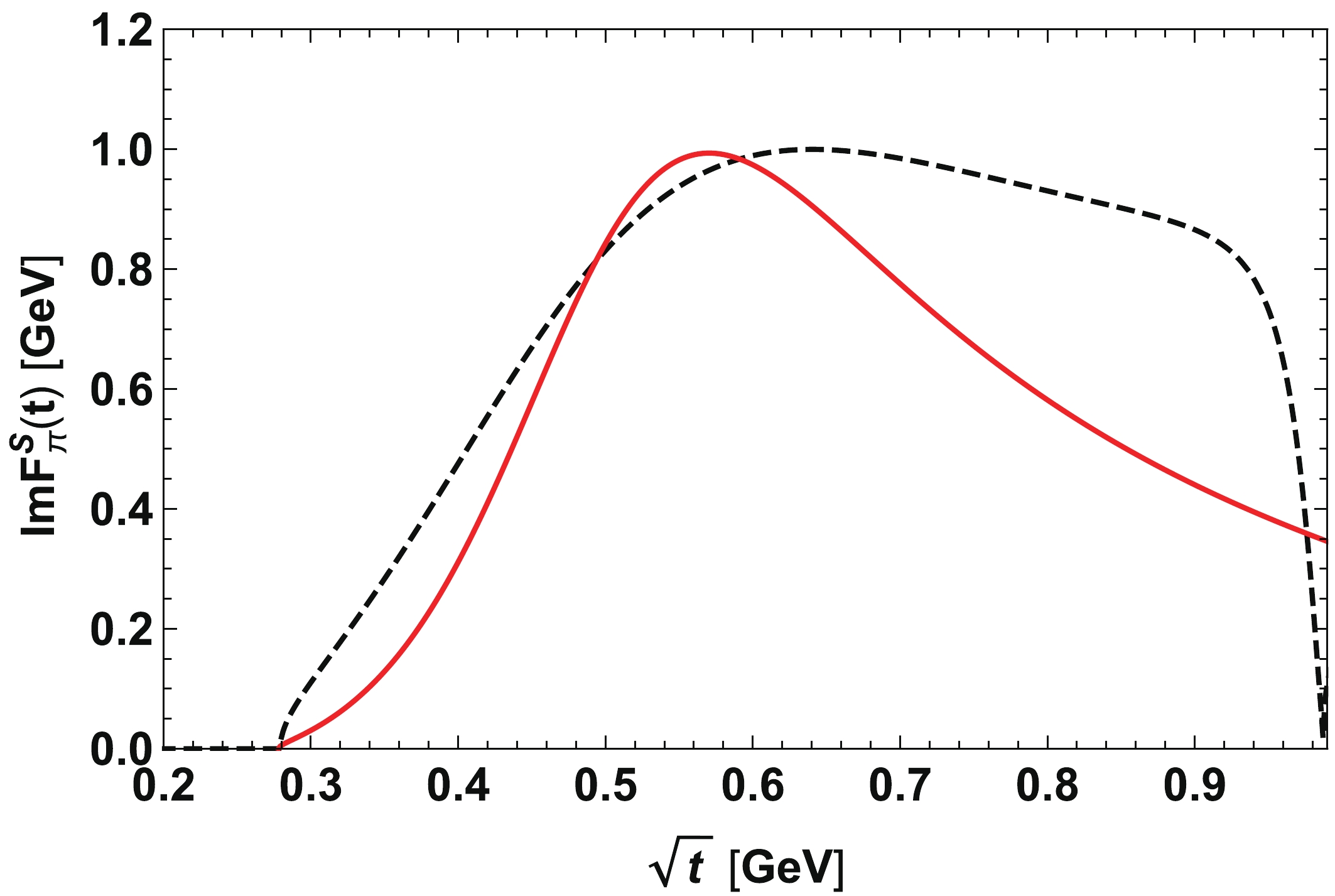

$ M_{\pi} = 0.139 $ GeV,$ F_{\pi} = 0.092 $ GeV, and$ g_{\sigma \pi \pi} = 2.52\,{\rm GeV} $ from the experimental value of$ \sigma $ width. Further, we use B = 0.7 GeV, but note that its precise value depends on the choice of the average quark mass. The coupling$ g_{\sigma} $ is merely used for normalization.In Fig. 2 we show the imaginary part of the scalar pion form factor in our approach in comparison to the dispersion-theoretical analysis of Ref. [14]. Up to

$ \sqrt{t} \simeq 0.6 $ GeV, the curves are very similar, but of course the$ f_0(980) $ contribution that causes the dip at$ \sqrt{t} \simeq 1$ GeV is not captured in our approach. Still, the visible enhancement due to the broad$ \sigma $ is clearly reflected in the imaginary part.

Figure 2. (color online) Imaginary part of the scalar pion form factor based on Eq. (6) (solid red line) in comparison to the dispersion-theoretical result of Ref. [14] (dashed black line).

-

In this section we focus on the calculation of the imaginary part of the isoscalar nucleon scalar form factor generated from the

$ \pi\pi $ intermediate states based on relativistic two-flavor baryon chiral perturbation theory. At lowest order in the quark mass and momentum expansion, the relevant interaction Lagrangians are given by [3, 15, 16]$ \begin{split} {\cal L}^{(1)}_{\pi N} =& \frac{g_A}{2}\bar{\Psi}\gamma^{\mu}\gamma_{5}u_{\mu}\Psi, \\ {\cal L}^{(2)}_{\pi N} = & c_1\langle\chi_{+}\rangle\bar{\Psi}\Psi-\frac{c_2}{4m_{N}^2}\langle u_{\mu}u_{\nu}\rangle (\bar{\Psi}D^{\mu}D^{\nu} \Psi+h.c) \end{split} $

$ \begin{split} & +\frac{c_3}{2}\langle u_{\mu}u^{\mu}\rangle \bar{\Psi} \Psi-\frac{c_4}{4}\bar{\Psi}\gamma_{\mu} \gamma_{\nu}[u^{\mu},u^{\nu}]\Psi + ..., \\ {\cal L}^{(2)}_{\sigma \pi \pi} =& g_{\sigma \pi \pi} \sigma \langle{u_\mu u^\mu}\rangle \,\, . \end{split} $

(7) Here,

$ \Psi $ denotes the nucleon doublet,$ \chi_{+} = u^\dagger \chi u^\dagger+u\chi^{\dagger}u $ , with$ \chi = 2B_0({\cal M}+ s) $ where s represents the external scalar source and$ \langle \ldots \rangle $ denotes the trace in flavor space. Further,$ g_A $ is the nucleon axial-vector coupling,$ g_A \simeq 1.27 $ , and the low-energy constants$ c_2, c_3 $ and$ c_4 $ are taken as$ c_{2} = 3.13 m_N^{-1} $ ,$ c_{3} = -5.61 m_N^{-1} $ and$ c_{4} = 4.26 m_N^{-1} $ [17]. These LECs are not affected by a contribution from the$ \sigma $ , see Ref. [8]. As already discussed in the introduction, the$ \sigma $ -meson contributes to the LEC$ c_{1} $ . We consider two extreme cases, namely$ c_{1} = 0 $ , which corresponds to a complete saturation of this LEC by the light scalar meson and$ c_{1} = 0.55 m_N^{-1} $ , which is half of the value given in Ref. [17]. This latter scenario leaves room for other contributions to this particular LEC.In addition to the scalar loop integrals in Eq. (5) we also need the integral of three-point function as

$ \begin{split}C_0(p_i^2, (p_f-p_i)^2, p_f^2, m_1^2, m_2^2, m_3^2) = \frac{(2 \pi \mu)^{4-n}}{i \pi^2}\int \frac{{\rm d}^nk}{[k^2-m_1^2 +i\epsilon^+][(k-p_i)^2-m_2^2+i\epsilon^+][(k-p_f)^2-m_3^2+i\epsilon^+]} \end{split} $

(8) with

$ q^2 = t = (p_f-p_i) $ and$ \epsilon^+ $ stands for$ \epsilon \to 0^+ $ . From these, the expressions for the imaginary part of the scalar form factor, which has dimension [mass], is given as$ \begin{split} {\rm Im}\; \sigma_{N}(t)\; =& \frac{B g_{\sigma} g_{\sigma \pi \pi}}{6 F_{\pi}^4 {\pi}^2 m_N} \Bigg(\frac{18 g_A^2 m_{N}^3}{4m_{N}^2-t}\Big((8m_{N}^2-2t)A_0(m_{N}^2)+(2M_{\pi}^2-t)(4m_N^2 M_{\pi}^2-2 m_N^2 t) {\rm Re}[{C_0(m_N^2, t, m_N^2, m_N^2, M_{\pi}^2, M_{\pi}^2)}]\\ &-t (2M_{\pi}^2-t)\, {\rm Re}[{B_0(t, M_{\pi}^2, M_{\pi}^2)}]+(16m_{N}^2 M_{\pi}^2-4m_N^2 t-2M_{\pi}^2 t) B_0(m_N^2, m_N^2,M_{\pi}^2)\Big)- 6 \Big (2 m_N^2 M_{\pi}^2(24 c_1-5c_2-24c_3) \end{split} $

(9) $ \begin{split}\\ \quad&+2t(m_N^2 c_2-M_{\pi}^2 c_2+6 m_N^2 c_3)+c_2 t^2 \Big) A_0(M_{\pi}^2)-\Big(8m_N^2 M_{\pi}^2(6c_1-c_2-3c_3)+2t(m_N^2 c_2+M_{\pi}^2c_2+6m_N^2c_3)+c_2 t^2\Big)(6M_{\pi}^2-3 t)\\&\times{\rm Re}[{B_0(t, M_{\pi}^2, M_{\pi}^2)}]+c_2\Big(66 m_N^2 M_{\pi}^4 + 4 m_N^2 t^2+8 M_{\pi}^2 t^2-32m_N^2 M_{\pi}^2 t-12 M_{\pi}^4 t-t^3 \Big)\Bigg)\\ &\times \frac{-M_{\sigma} \Gamma_{\sigma}(t) }{t^2+M_{\sigma}^4-2 M_{\sigma}^2 t + M_{\sigma}^2 \Gamma_{\sigma}^2 (t)} \end{split} $

(9) where the

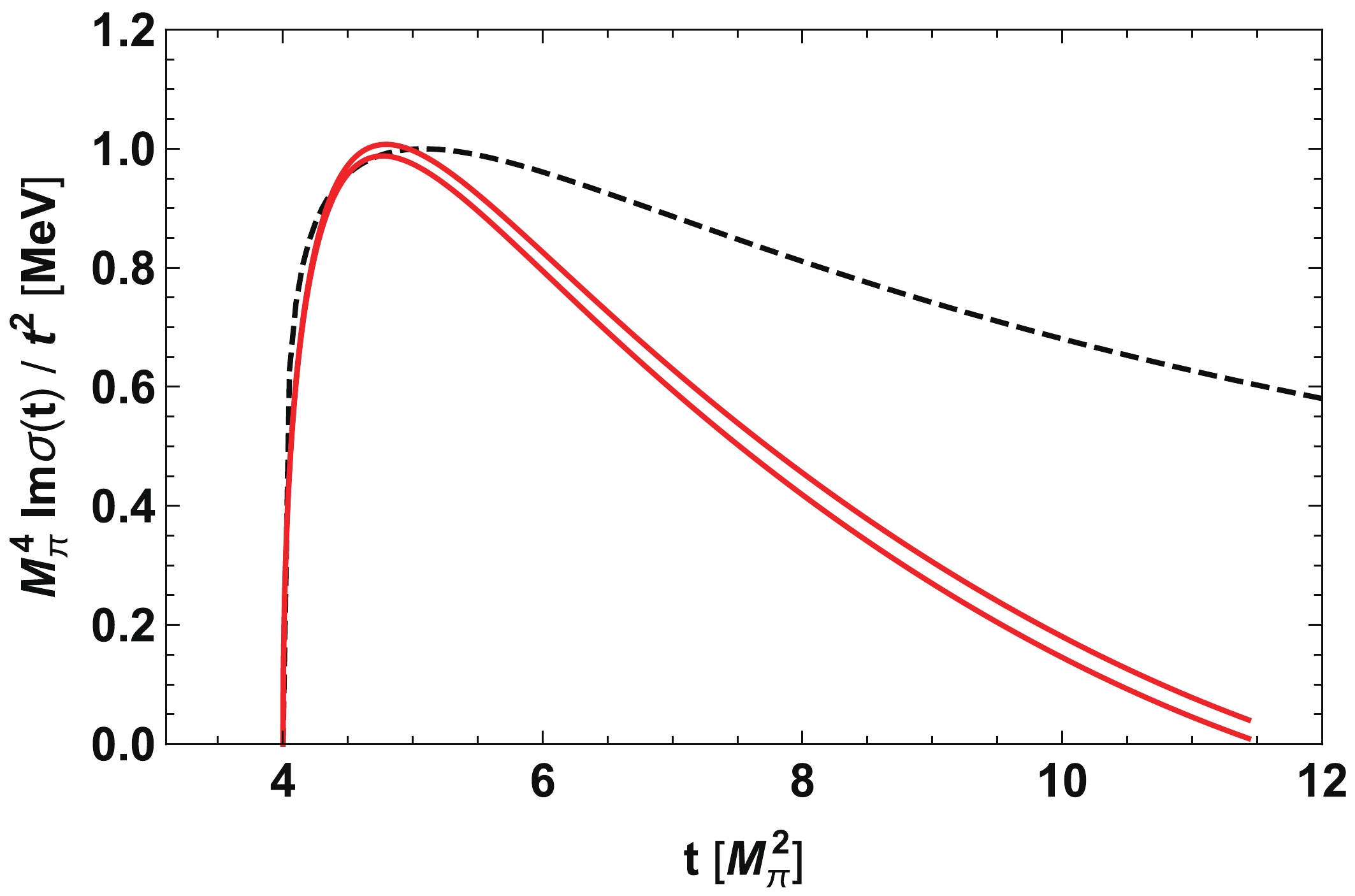

$ A_0(m^2) $ and$ B_0(m_1^2, m_1^2, m_2^2) $ functions are real.The resulting weighted spectral function

$ M_{\pi}^4 \,{\rm Im}\; \sigma(t)/t^2 $ is shown in Fig. 3 for the case of complete saturation$ c_1 = 0 $ (lower solid red line) and the one of partial saturation ($ c_1 = -0.55 m_N^{-1} $ ) (upper solid red line) in comparison to the two-loop heavy baryon chiral perturbation theory results of Ref. [18]. We see that the explicit$ \sigma $ -meson contribution drops faster than the pion loop contribution, showing that the$ \sigma $ does not saturate this imaginary part.

Figure 3. (color online)

$ \sigma$ -meson contribution (solid lines) to the isoscalar spectral function of the scalar nucleon form factor multiplied with$ M_\pi^4/t^2$ , compared with the two-loop chiral perturbation theory result of Ref. [18] (black dashed line). The lower (upper) solid line refers to the case of complete (partial) saturation of the LEC$ c_1$ as discussed in the text. -

In this note, we have considered the broad

$ \sigma $ -meson contribution to the scalar form factors of the pion and the nucleon, respectively. In the pion case, the imaginary part clearly exhibits the$ f_0(500) $ contribution, but below$ \sqrt{t} \simeq 1 $ GeV, one also needs to include the$ f_0(980) $ . The latter is responsible for the pronounced dip in the imaginary part. Concerning resonance saturation, just including the scalar mesons around 1 GeV is not sufficient, though one can produce the light scalar as a rescattering effect through pion loop resummation. This, however, requires a non-perturbative framework. Similarly, for the scalar nucleon form factor, we find that the$ \sigma $ -meson saturates the imaginary part at low invariant momenta but drops faster than the two-loop contribution. This is similar to the findings in Ref. [8], where it was shown that the leading scalar-isoscalar low-energy constant$ c_1 $ can only be explained in terms of scalar meson exchange for a very special combination of ratio of the sigma-nucleon coupling constant to the$ \sigma $ mass. As the calculations presented here underline, the broad$ \sigma $ -meson enjoys a very special role in low-energy QCD.We thank Norbert Kaiser and Bastian Kubis for providing us with their results. We are also grateful for the referee for a pertinent comment.

A note on scalar meson dominance

- Received Date: 2019-08-13

- Available Online: 2019-10-01

Abstract: We consider chiral perturbation theory with an explicit broad σ-meson and study its contribution to the scalar form factors of the pion and the nucleon. Our goal is to learn more about resonance saturation in the scalar sector.

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: