-

Nuclear matter under extreme pressure and temperature conditions is of particular interest, as its properties and evolution can shed light on quantum chromodynamics (QCD). High-energy heavy-ion collisions have been used to create possibly deconfined quark matter, which could have existed a few microseconds after the Big Bang. Among the final states, the light nuclei production is a sensitive probe of their production mechanism and the properties of system evolution [1, 2]. They can be used to extract information on nucleon correlations and density fluctuations in heavy-ion collisions, which may provide crucial insights for the space-time evolution of the collision and searching for a possible critical point [3−6]. Light nuclei may also abundantly appear in stellar objects such as supernova and binary neutron star mergers [7, 8]. Their presence may impact the evolution and equation-of-state of these systems by affecting the transport coefficients in the dissipative process and the neutrino emission [9, 10]. Another reason to study light nuclei production in heavy-ion collisions is the investigation of anti-nucleus's origin in comic rays [11, 12]. In the AMS-02 experiment [13] in the International Space Station, anti-nuclei flux may have been observed in space [14]. It is debated whether these events come from dark matter annihilation or anti-matter in space. The answer depends on the background estimates from

$ p-p $ and$ p-A $ collisions [11, 12].Currently, there are several popular but very different theoretical models describing the mechanism of light nuclei production in high-energy heavy-ion collisions. The statistical model depicts the light nuclei as thermally produced during the hadronization, and the total yields of light nuclei do not change after chemical freeze-out [1, 15]. The statistical model has successfully described the yields of light nuclei and yield ratios of different light nuclei species [16−18]. While the binding energy of light nuclei is around several MeV, the thermal model cannot explain the survival of these loosely bounded nuclei in the fireball, in which the temperature near chemical freeze-out is approximately 100 MeV [16]. The nucleon coalescence model assumes that light nuclei are formed at the late stage near the kinetic freeze-out of the fireball evolution via the coalescence of nucleons when these constituent nucleons are close to each other in both the coordinate space and momentum space [19, 20]. The coalescence picture has been used for understanding the light nuclei yields and flow from the STAR experiment at

$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}=3-200 $ GeV [21−23]. Additionally, dynamical formation and dissociation of light nuclei based on kinetic nuclear reactions have been used to explore the light nuclei production for many years [24, 25]. With the recent inclusion of light nuclei size in the relativistic kinetic equations, the light nuclei yield in both$ p+p $ and Au+Au (Pb+Pb) can be well described [26].This paper discusses the light nuclei production in Au+Au collisions at

$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}=3 $ GeV by utilizing a simple nucleon coalescence model. The nucleons are produced via the Jet AA Microscopic Transport Model (JAM) [27]. The aim of such calculations is to investigate the coalescence parameter dependencies on different light nuclei species. The light nuclei transverse momentum$ p_{\rm T} $ spectra from the coalescence calculations are compared with the data measured by STAR [28]. This study will provide an improved understanding of coalescence calculations and light nuclei formation mechanisms in heavy-ion collisions. -

The JAM is designed to simulate relativistic nuclear collisions from the initial stage of nuclear collision to the final state interaction at finite and high baryon densities [27, 29]. In the model, the initial position of each nucleon is sampled by the distribution of nuclear density, and the nuclear collision is described by the sum of independent binary hadron-hadron collisions. At low energies (

$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}<4 $ GeV), inelastic hadron-hadron collisions produce resonances that can decay into hadrons. All the established hadronic states and resonances can propagate in space and time and interact with each other via binary collisions. The JAM has both a cascade mode and a mean-field mode. In the cascade mode, each hadron is propagated as in the vacuum between collisions with other hadrons. In the mean-field mode, the nuclear equation-of-state effects have been included through a momentum-dependent potential acting on the particle propagation [30]. The calculations from the mean-field mode have successfully described the light nuclei flow measurements at$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}=3 $ GeV Au+Au collisions, while the cascade mode failed to explain the data [23]. In our analysis, we use the JAM in its mean-field mode (incompressibility parameter$ \kappa= $ 380 MeV) to generate the Au+Au collision events.We obtain phase-space distributions for protons and neutrons from the JAM for Au+Au collisions at

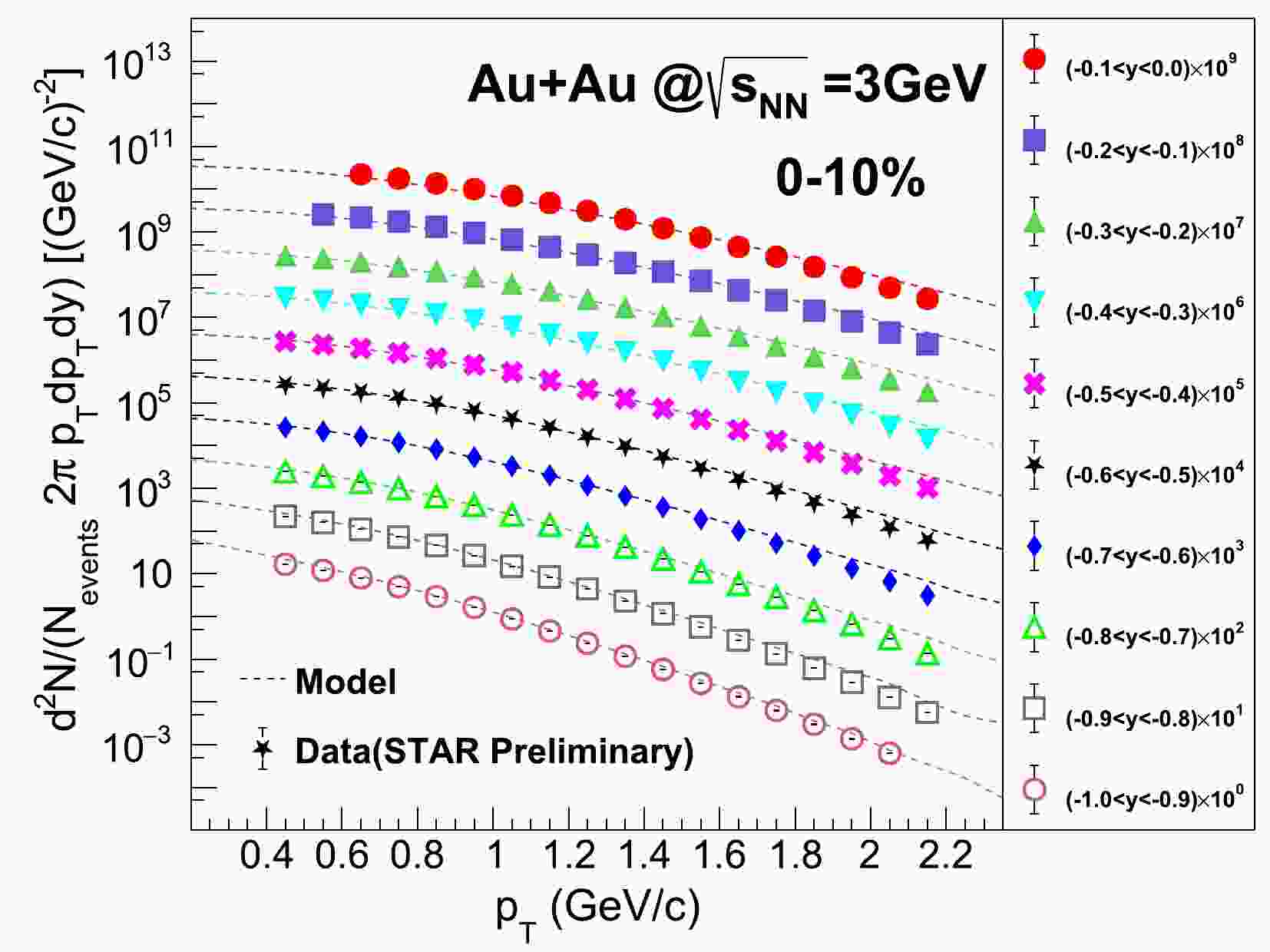

$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}=3 $ GeV. Figure 1 shows the$p_{T}$ distribution of protons in various rapidity (y) intervals at 0%−10% most central collisions. The proton (p)$p_{T}$ spectra generally agree with the data measured by the STAR experiment [28] at$p_{T} < 1.4$ GeV/c for all rapidity intervals. However, the model calculations overestimate the data in the higher$p_{T}$ region.

Figure 1. (color online) Proton

$p_{T}$ spectra from the JAM calculations (solid lines) in various rapidity bins for 0%−10% Au+Au collisions at$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}=3 $ GeV. Markers represent data measured by the STAR experiment.The JAM does not produce light nuclei. Therefore, we utilize a simple afterburner coalescence to form deuteron (d), triton (t),

$ ^3 $ He, and$ ^4 $ He. In an event from the JAM, the positions and momentum of p and neutron (n) are recorded at a fixed time of 50 fm/c at which nearly all the nucleons are kinetically frozen out. Each$ (p,n) $ pair is boosted to its rest frame, and then one obtains its relative space distance$ \left|R_{1}-R_{2}\right| $ and relative momentum difference$ \left|P_{1}-P_{2}\right| $ . If both the values satisfy$ \left|R_{1}-R_{2}\right|< \Delta R $ and$ \left|P_{1}-P_{2}\right|< \Delta P $ , where$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ are required values for d formation, this$ (p, n) $ pair is marked as a d. For a t formation, a$ (p, n) $ pair is first formed according to the$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ of t, and then one additional n is included, and we calculate its relative space distance and momentum difference from the formed$ (p, n) $ pair. The$ ^{3} $ He and$ ^{4} $ He are formed similarly with different$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ . This simple form of coalescence at a fixed time can be improved by using the wave function of light nuclei [31, 32]. However, the phase space coalescence worked successfully [23] and gave results similar to those obtained via the wave function approach [33]. Therefore, we utilize the simple coalescence method to provide qualitative results for coalescence parameters$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ of different light nuclei species.To determine the values of

$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ that have the best descriptions for the light nuclei$ p_{T} $ spectra, we carry out the scan of$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ for each light nuclei species, in which$ \Delta R $ is varied from 2 to 6$\rm fm$ with a step length of 0.2$\rm fm$ and$ \Delta P $ is varied from 0.1 to 0.5 Gev/c with a step length of 0.04 Gev/c.Under the assumption that n has the same phase space distribution as p in the collisions, the invariant distribution of light nuclei can be expressed by the following equation:

$ \begin{split} E_{A} \frac{{\rm d}^{3} N_{A}}{{\rm d}^{3} p_{A}} & \propto\left(E_{p} \frac{{\rm d}^{3} N_{p}}{{\rm d}^{3} p_{p}}\right)^{Z}\left(E_{n} \frac{{\rm d}^{3} N_{n}}{{\rm d}^{3} p_{n}}\right)^{A-Z} \\ & \approx \left(E_{p} \frac{{\rm d}^{3} N_{p}}{{\rm d}^{3} p_{p}}\right)^{A}, \end{split} $

(1) where A represents the atomic mass number. Because the

$p_{T}$ spectra of the proton from the JAM calculations overestimate the data at high$p_{T}$ , as shown in Fig. 1, the discrepancy with the model will be enhanced by a power factor of A for light nuclei with a mass number of A according to Eq. (1). To reduce the impact on the determination of coalescence parameters, the$p_{T}$ spectra for light nuclei are corrected following Eq. (2). The yield ratio of data to the model calculation is obtained in a given$(p_{T}, y)$ cell of proton results, and then the light nuclei yield from the model calculation is corrected by the A-th power of the factor in the$(A p_{T},y)$ cell.$ \begin{equation} \frac{{\rm d} N_{\text {data }}^{A}}{{\rm d} N_{\text {model }}}\left(A p_{T}, y\right)=\left(\frac{{\rm d} N_{\text {data }}^{p}}{{\rm d} N_{\text {model }}}\left( p_{T}, y\right)\right)^{A}. \end{equation} $

(2) For light nuclei in a given rapidity interval, the

$p_{T}$ range for applying the correction is determined by the$p_{T}$ coverage of the data points of the proton. -

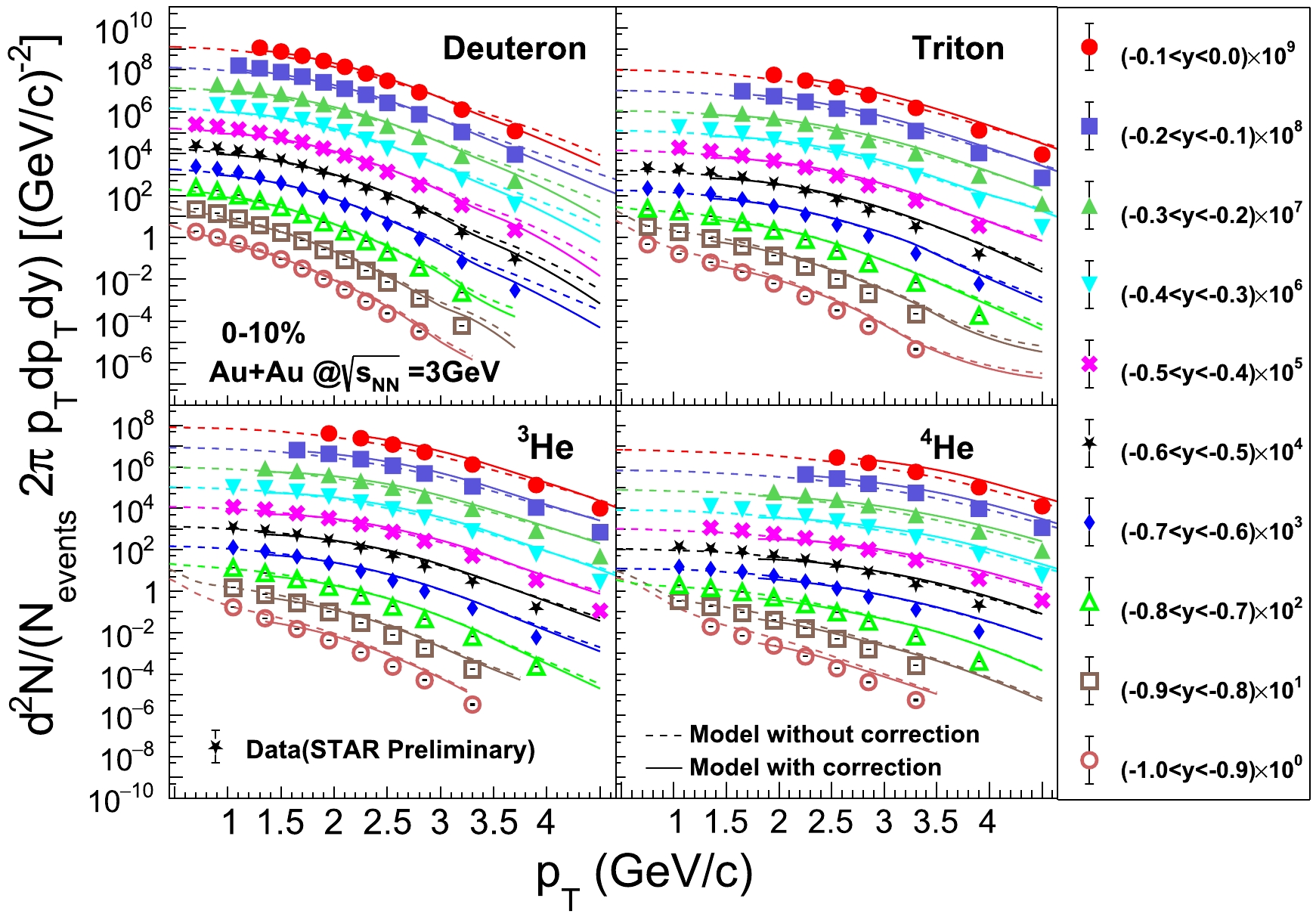

Figure 2 shows the

$p_{T}$ spectra for d, t,$^{3}\rm He$ , and$^{4}\rm He$ in various rapidity bins in 0%−10% Au+Au collisions at$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}=3 $ GeV. The results of the model calculations are obtained using the coalescence parameters$\Delta R=4.0~\rm fm$ and$ \Delta P=0.3 $ GeV/c. The distributions with and without the correction based on Eq. (2) are indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively. After the correction, the model calculations qualitatively reproduce the experimental data for all light nuclei species, including the high$p_{T}$ region. This supports the validity of using the simple coalescence approach for light nuclei production in heavy-ion collisions at several GeV.

Figure 2. (color online)

$p_{T}$ spectra for d, t,$ ^3 $ He, and$ ^4 $ He data measured by the STAR experiment and calculations from the JAM. Markers represent data. The dashed and solid lines represent the model calculations without and with corrections based on Eq. (2), respectively. The cut-off for the correction result is caused by the low limit of proton$p_{T}$ in the data.Near the target rapidity

$ y=-1.045 $ , the fragmentation of the target ions may also contribute to the production of light nuclei. Currently, most transport models are unable to describe the production of the fragments in high-energy heavy-ion collisions. Meanwhile it is found that our calculations can match the$p_{T}$ spectra of light nuclei at the target rapidity with the same coalescence parameters as for the mid-rapidity at 0%−10% centrality, where the light nuclei are believed to be formed mainly through the nucleon coalescence. This agreement can be understood using a simple picture. In the collisions, the protons and neutrons near the target rapidity are less affected by the system evolution compared with those at the mid-rapidity; their momentum magnitude and direction will remain close to each other. Thus, the nucleons near the target rapidity have a higher chance to combine, and the light nuclei production will be enhanced compared with the mid-rapidity, especially for$ ^4 $ He. Meanwhile, at peripheral collisions, the contribution of fragments near the target rapidity become more important [28]; thus, the model calculations no longer match the data.The light nuclei

$p_{T}$ spectra in each rapidity interval obtained with a chosen ($ \Delta R, \Delta P $ ) are compared with the data using the$ \chi^{2} $ $ \begin{equation} \chi^{2}=\sum_{ p_{T}} \left(\frac{v_{\rm data}-v_{\rm {model}}}{e_{\rm data}}\right)^{2}, \end{equation} $

(3) where

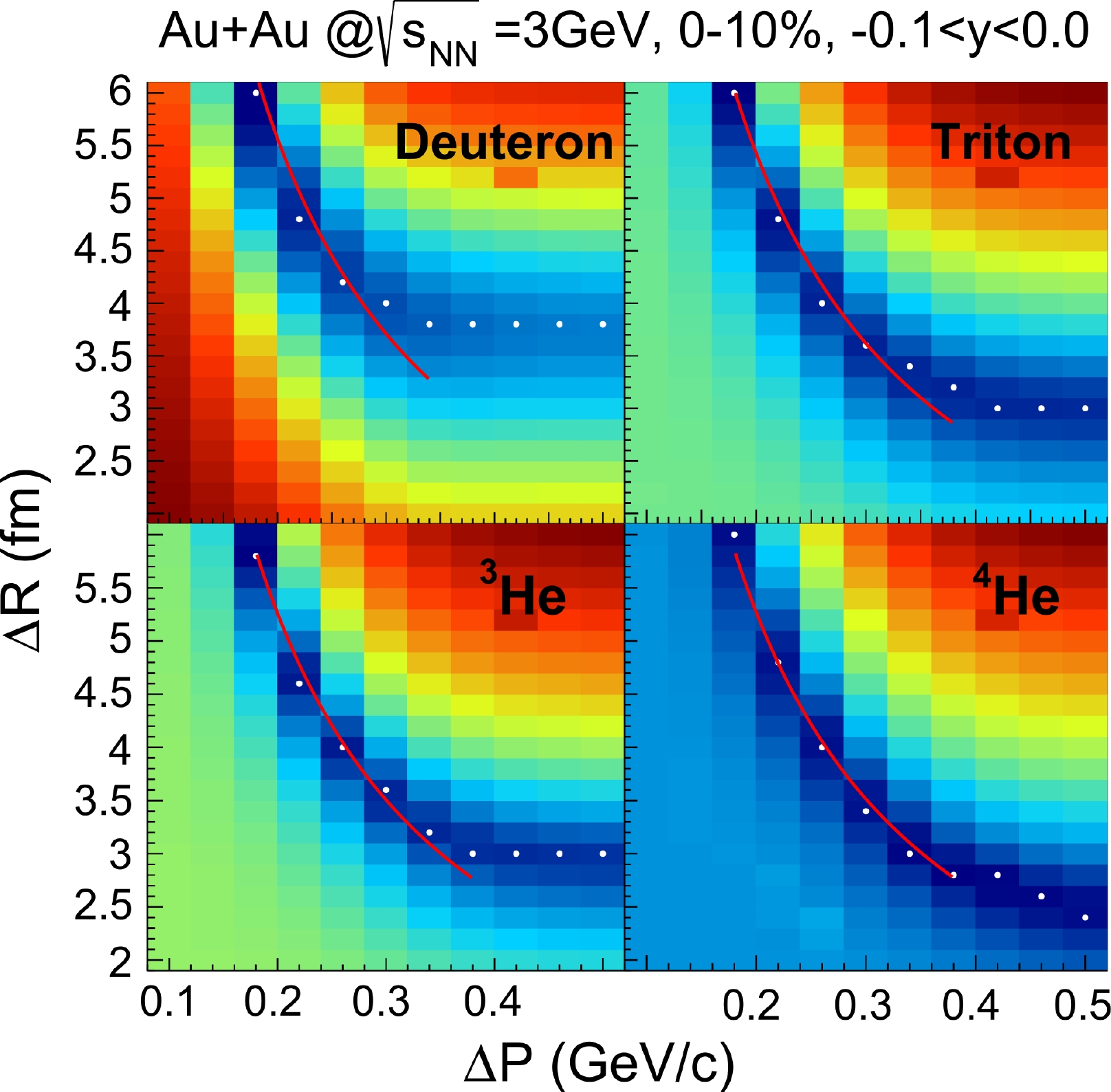

$ v_{\rm data} $ and$ e_{\rm data} $ represent the light nuclei yield and its statistical uncertainty measured by the STAR experiment, and$ v_{\rm {model}} $ represents the model calculation for light nuclei yield with the correction based on Eq. (2). If the model has a better overall description of the data, the extracted$ \chi^2 $ will be smaller.Figure 3 shows the dependencies of the

$ \chi^{2} $ on the$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ at the mid-rapidity$ -0.1<y<0 $ in 0%−10% Au+Au collisions at$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}=3 $ GeV. The minimum position of the$ \chi^2 $ can be constrained by the$ \Delta R $ in a given$ \Delta P $ bin for all the studied light nuclei species, especially for d owing to its large number of data points and small statistical errors. At low$ \Delta P $ , the$ \Delta R $ for the minimum$ \chi^2 $ decreases with an increase in$ \Delta P $ , while the product$ \Delta R\cdot \Delta P $ remains nearly unchanged; the corresponding values are 1.2 for d and t and 1.15 for$ ^3 $ He and$ ^4 $ He. Following$ \chi^2- $ minimization, the$ \Delta R $ is constant in the high$ \Delta P $ region for d, t, and$ ^3 $ He, which means that the light nuclei yields will not increase with an increase in$ \Delta P $ . The values of ($ \Delta R, \Delta P $ ) at the minimum$ \chi^2 $ are ($ \Delta R=5.6 $ fm,$ \Delta P=0.22 $ GeV/c) for d, ($ \Delta R=5.6 $ fm,$ \Delta P=0.22 $ GeV/c) for t, ($ \Delta R=5.2 $ fm,$ \Delta P=0.22 $ GeV/c) for$ ^3 $ He, and ($ \Delta R=3 $ fm,$ \Delta P=0.42 $ GeV/c) for$ ^4 $ He at$ -0.1 <y<0 $ . For each light nuclei species, the$ \chi^2 $ distributions in other rapidity bins are very similar to the one in Fig. 3, and the ($ \Delta R, \Delta P $ ) extracted using$ \chi^2- $ minimization has no strong dependence on the particle rapidity. The average values of$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ in all the rapidity bins are ($ \Delta R=5.78 $ fm,$ \Delta P=0.219 $ GeV/c) for d, ($ \Delta R=5.43 $ fm,$ \Delta P=0.237 $ GeV/c) for t, ($ \Delta R=5.24 $ fm,$ \Delta P=0.242 $ GeV/c) for$ ^3 $ He, and ($ \Delta R=4.585 $ fm,$ \Delta P=0.3 $ GeV/c) for$ ^4 $ He. A weak dependence of$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ on the light nuclei rapidity implies that light nuclei are formed after the cascade stage of the reaction in high-energy heavy-ion collisions.

Figure 3. (color online) Dependencies of

$ \chi^2 $ on the coalescence parameters ($ \Delta R, \Delta P $ ) for d, t,$ ^3 $ He, and$ ^4 $ He within$ -0.1 < y <0 $ in 0%−10% Au+Au collisions at$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}=3 $ GeV. The dots represent the minimum position of$ \chi^2 $ for a given$ \Delta P $ . The solid lines are the fits to these minimum values with an inversely proportional function.Figure 4 shows the extracted

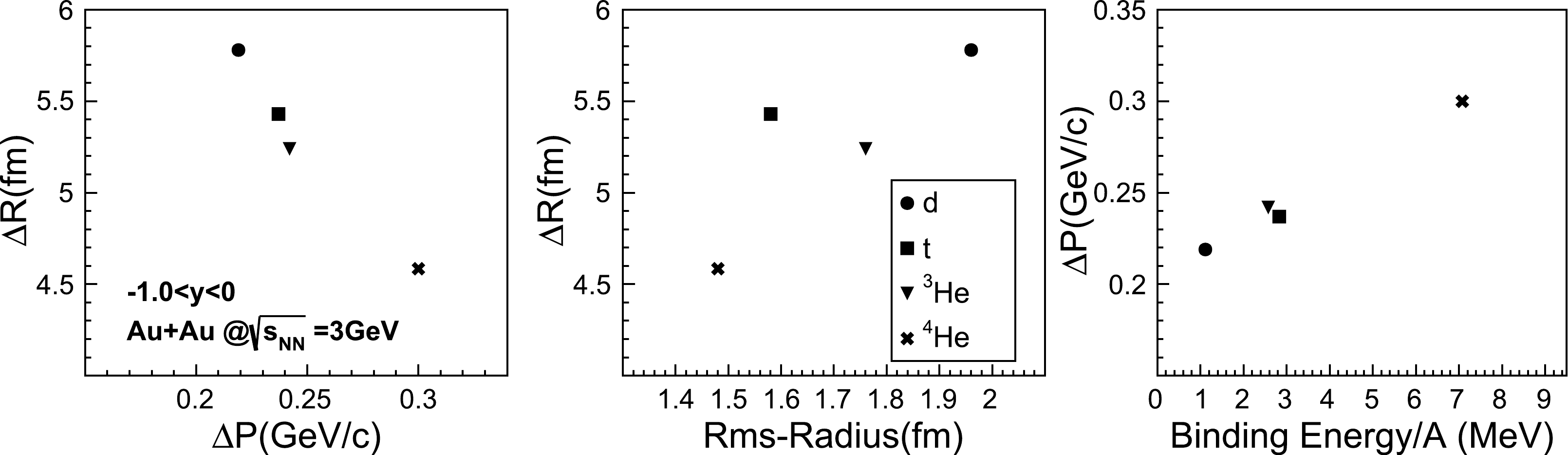

$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ with the minimum$ \chi^2 $ describing the data in all rapidity bins at 0%−10% centrality, as well as their dependencies on the nuclei diameter and binding energy [34]. Among the studied light nuclei species, d has the largest$ \Delta R $ and smallest$ \Delta P $ , while$ ^4 $ He exhibits the opposite trend. In the middle and right panels of Fig. 4,$ \Delta R $ is almost positively associated with the nuclei diameter, and$ \Delta P $ is positively correlated with the nuclei binding energy. This suggests that nuclei with lower binding energies can be formed with a higher upper limit for the relative momentum difference between their component nucleons.$ ^3 $ He and t have very similar$ \Delta P $ and$ \Delta R $ , as both their radii and binding energies are close. This investigation indicates that the radius and binding energy of light nuclei are crucial for their formation in heavy-ion collisions.

Figure 4. Left:

$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ of the minimum$ \chi^2 $ in all rapidity bins for d, t,$ ^3 $ He, and$ ^4 $ He. Middle:$ \Delta R $ as a function of the nuclei rms diameter. Right:$ \Delta P $ as a function of the nuclei binding energy per nucleon.The

$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ are supposed to be unique for a given nuclear species; thus, they are expected to be independent of the collision system and energy. This enables us to repeat the calculations for other collision energies with the same parameter sets and predict the light nuclei spectra and collective behavior. In this simple coalescence model, the formed light nuclei will sustain the collective flow of the produced nucleons, which are expected to be sensitive to the initial pressure gradient of the collision system. Light nuclei are heavier than nucleons, and their collective flow has stronger energy dependence according to the coalescence model [23] and thus is more sensitive to the change in pressure or the equation-of-state (EoS). Work in this direction is ongoing. -

In summary, the light nuclei d, t,

$ ^3 $ He, and$ ^4 $ He are formed via the phase space coalescence of nucleons produced by the JAM in a mean field mode at$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}=3 $ GeV Au+Au collisions. We investigate the cut-off of the coalescence parameters$ \Delta R $ and$ \Delta P $ by comparing the calculations with the data measured by the STAR experiment. For a given light nuclei species, a unique ($ \Delta R $ ,$ \Delta P $ ) is obtained, which can describe the$p_{T}$ spectra both at the mid-rapidity and at the target rapidity at 0%−10% centrality. The result implies that at central collisions, the nucleons near the target rapidity may have a higher coalescence probability than those at the mid-rapidity, as they are less affected by the system expansion. It is found that$ \Delta P $ and$ \Delta R $ are nearly positively correlated with the nuclei binding energy and nuclei diameter, respectively. The result suggests that the radius and binding energy of light nuclei are crucial for their formation in heavy-ion collisions.

Light nuclei production in Au+Au collisions at ${ \sqrt{{\boldsymbol s}_{\boldsymbol N \boldsymbol N}}} \boldsymbol{=}$ 3 GeV from coalescence model

- Received Date: 2022-12-16

- Available Online: 2023-07-15

Abstract: The nucleon coalescence model is one of the most popular theoretical models for light nuclei production in high-energy heavy-ion collisions. The production of light nuclei d, t,

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: